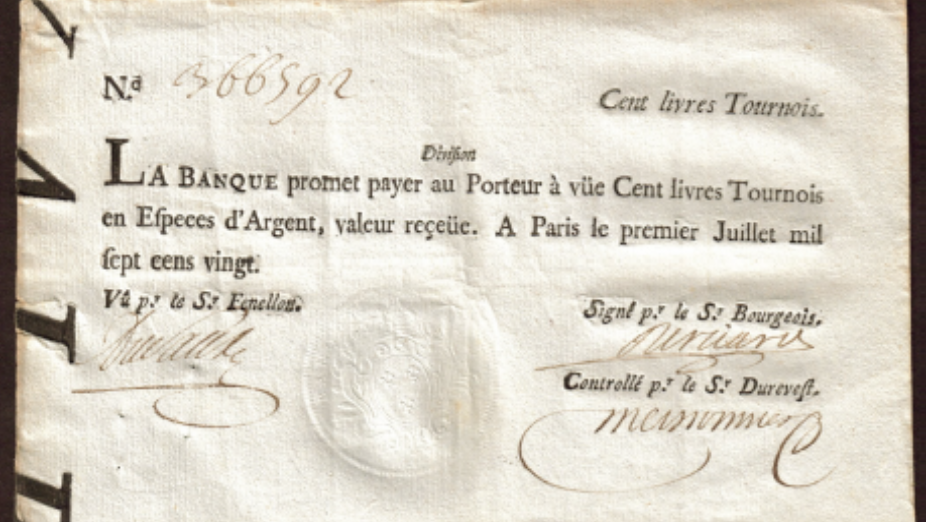

A 100-Livres banknote issued by the Banque Royale on July 1, 1720. This bill was issued at the height of the speculative mania with the Mississippi Company stocks. (Image from: John E. Sandrock, John Law’s Banque Royale and the Mississippi Bubble - http://www.thecurrencycollector.com/)

A 100-Livres banknote issued by the Banque Royale on July 1, 1720. This bill was issued at the height of the speculative mania with the Mississippi Company stocks. (Image from: John E. Sandrock, John Law’s Banque Royale and the Mississippi Bubble - http://www.thecurrencycollector.com/)

Exactly 50 years ago—on August 15, 1971—U.S. President Richard Nixon abolished the exchange of dollars for gold in a short, televised speech. Ever since, central banks have been issuing unbacked, purely paper money, bound by no ties to currency-independent values. The real value of the dollar has also fallen to as little as 15% of what it was before this shift. There has been gross monetary trickery, promises have been broken, the modern age of money manipulation has begun.

These recent monetary experiments follow to the letter the procedure of one of the greatest money tricks in history: the paper money experiment of John Law in France in 1716-1720.

The EU powers put the new euro currency into circulation 22 years ago, and since then it has already lost 31% of its value. The money tricksters are also making their rounds in Germany, because the new euro was presented as a currency just as solid as the old Deutschmark. The American Fed and the European central bank (ECB) have multiplied the money in circulation since the financial crisis of 2008—and new signs of inflation are already appearing. Citizens far and wide are holding their breath; they sense that this is not going to end well.

The Seduction of Cheap Money

They do not realize that these recent monetary experiments follow to the letter the procedure of one of the biggest money tricks in history: the paper money experiment of John Law in France from 1716-1720. It is no coincidence that some of today’s monetary theorists call it “modern” and groundbreaking: a fact that is deeply disturbing.

The experiment goes like this:

The Fed and the ECB buy up government debt securities from governments that are in reality insolvent, and the governments give the banks new money in return. This is exactly what the Scotsman John Law proposed to the regent of France, Philippe d’Orléans, to avert the impending state bankruptcy.

Law founded the Banque Générale, a precursor of central banks. The public received their new type of paper money by selling the government debt securities in their possession to the Banque Générale, at the full value written on them. This was because creditors had long since ceased to trust the French state, and government debt was only traded at 60%. Banque Générale thus became the state’s sole creditor, and the public suddenly had a lot of cash in its hands in the form of paper money. Everyone was happy—the state as well as the public.

After all, the Sun King’s previous wars and the country’s trade deficits had drained a lot of gold; and money, in the classic metallic sense, had become scarce. Trade and exchange suffered. Then along came John Law, and suddenly the public got hold of money quite easily. They could also buy the shares of the Banque Générale and even get loans from it to buy its shares. John Law lowered the interest rate on the remaining government securities and directed the holders—nobility, monasteries, and foundations—to shares, whose prices rose, and which represented a substitute.

The Fed and ECB are doing the same with zero interest rates and expansions of the money supply used to buy up shares—people are supposed to get their yields from the stock markets. Stock prices have also been rising for years.

A Source of Money for the Rich and Powerful, a Bailout for Politicians and Budget Excesses

John Law was happy: he had saved the parasitic royal court from bankruptcy; he became a courtier; his initially private “Banque Générale” became the “Banque Royale” in 1718; and more and more printed money gushed forth for the rich and powerful. Law now also became finance minister. He was granted a monopoly on coinage for his Banque in 1719, and in February 1720 he finally merged it with the colonial company “Compagnie des Indes,” into which he had previously incorporated the famous “Mississippi Company.” To make the issued shares credible, this super company received indirect taxes as well as the rest of the nation’s taxes signed over as income. Thus, Law was now an entrepreneur, owner of a trade monopoly, head of the central bank, and supreme fiscal authority all in one.

The same thing is happening in the eurozone. The ECB is buying up government debt in huge quantities. Their prices rise far above the crisis values of Italian, Greek, Spanish, and Portuguese debts in the euro crisis of 2010, and the interest rates on them fall, in some cases even becoming negative. But the holders and sellers of the sovereign debt have been able to push themselves into good health, as they say in stock market parlance, through the increased prices of precisely these government securities, and finally through the unearthly stock market boom.

Like Law, former ECB chief Mario Draghi bailed out a compromised caste of politicians, their budget excesses, and their immature new currency.

Like Law, former ECB chief Mario Draghi bailed out a compromised caste of politicians, their budget excesses, and their immature new currency. The eurozone institutions then banded together like John Law’s super-conglomerate. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM), founded as a bailout fund in the Southern European crisis of 2012, is now a bank and just created a 500-billion-euro line of credit for the southern European countries out of thin air. The EU wants to borrow 750 billion euro to make gifts and investments to the southern members, and another trillion for coming budget deficits of the EU itself: here, too, it was promised to secure these burdens with taxes coming to the EU in the future.

John Law wrote in 1715:

“I maintain that an absolute prince who knows how to govern can extend his credit further and find needed funds at a lower interest rate than a prince who is limited in his authority.”

- John Law, Mémoire sur les banques, présenté a son altesse royale Monseigneur le duc d’Orléans. English translation of quote taken from Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money (New York: Penguin Books, 2009), 140.

The over-indebted euro states, alongside Germany, always guarantee everything in turn. And since March 2020, as announced at the time, the ECB has been buying up new, enormous quantities of these debt securities. By negative interest on deposits (thus by gradual “amputation” of their value) it drives their owners, i.e., the public, to purchase securities, shares, and other investments. Likewise, to move these funds into the economy, the banks in turn receive loans from the ECB at negative interest rates, that is, they are subsidized by it. As was the case with John Law, the bank thus pays the public to make use of paper money.

First Against the Force of Economic Law and then, Ultimately, Coercive Measures

To compel those who resisted his monetary system, Law decreed first that all major transactions were to be made in paper money, followed by decreeing that all transactions were. What the ban on cash for payments greater than 10,000 euros (Italy 1,000 euros) represents today in the eurozone, was then this ban of the older “cash”, i.e., gold and silver. Like John Law’s paper money machine back then, today the central banks force everyone under their monopoly. And the prices of securities, bank creditworthiness, money value, government deficits, central banks, and euros are all interlocked and intertwined. Today, this is called a “doom loop” or a “vicious circle.” If one falls, then they all fall together.

But back then, in 1720, the public’s common sense kicked in, and the laws of economics prevailed. In reality, they were the same laws that John Law first used—namely, that the value of money depends on its quantity and acceptance by the public. But the Banque Royale had continuously issued new money and new shares under pressure from politically influential people. Today, politicians are also twisting the arms of central banks—in the EU with the aforementioned 1.75 trillion in new debt securities, and in the U.S. with the Biden administration’s trillion-dollar packages. In John Law’s time, it also became a feast of millions that reached twice the national product of France. Prices began to skyrocket rapidly, the value of paper money began to crumble, and some merchants in Paris began once again to accept only gold and silver coins.

This marked the path that the Fed and the ECB would eventually take out of necessity, resorting to initially unplanned coercive measures.

This marked the path that the Fed and the ECB would eventually take out of necessity, resorting to initially unplanned coercive measures. John Law became nervous. He began to improvise; he became authoritarian, and he banned private gold and silver ownership (as the U.S. did in 1934, and as England did in 1967). To prop up Banque Royale prices, he offered to buy up everything—stocks, precious metals, and residual government debt. Thus, the money supply swelled immeasurably.

Panic and Eventual Reversal—At the Expense of Creditors

With all this paper, everyone bought what still promised real value: real estate, jewelry, horses, and works of art. Then Law embarked on a currency reform—the paper notes were to be exchanged two for one, their value thus halved. Then, to show the public that the money supply was being reduced, he had paper money burned every day in front of City Hall. Seeing this, however, the public understood only one thing: paper is no longer worth anything. Riots, looting, and murders were the result—civilization disintegrated with alarming speed. A ban on foreign trips and on capital export was imposed, as happened in Greece during its last crisis.

In the end, only one policy remained: immediate reversal. The state itself issued debt securities again, which bore normal interest, and thus a lot of paper money returned to the banque and was stamped out. But these paper and securities offered by the public were simply authoritatively reduced in value; no one got the inflated value. The equally inflated bonds, the counterparts of the former government debt, were frozen for three years, no one could return them, and as a dot on the i, these creditors were slapped with a forced loan. But it was guaranteed in gold and silver and carried an interest rate of 4%.

The Fed and the ECB: Driven by Their Own Impulses

With all these coercive measures, the flood of money was tamed and finally contained. Someday, the Fed and the ECB will also have to use authoritarian measures to neutralize the huge amounts of money created, which lie in the accounts of the vaults at these central banks, with reductions in value, the harbingers of which are the negative interest rates; with the exchange into other values or even into a new currency; with high minimum reserves of the banks at the central bank, in order to neutralize the money there; with prohibitions of capital exports; and with maximum interest rate regulations for government debt securities, as in the USA after 1945. They will try to hold back the overproduced money of the banks in the central bank accounts by offering them promissory bills for it at better interest rates than on the market. Instead of pushing down interest rates, they will then raise them. They will create their own problems.

That the economy can only run with high monetary liquidity, as John Law or later John M. Keynes assumed, is a fairy tale. The entire industrial revolution up to 1914 took place under the gold standard.

Perhaps, like the period following John Law or that which followed the Weimar Republic, central banks will again have to tie money to real things to restore confidence following inflation.

France plunged into a severe economic crisis after the failure of the paper money experiment; banks and monetary transactions became suspect. France’s elite, the corporations, and the state, once again lived only on land revenue and thus missed the industrial revolution.

In the Vast Gallery of Money Manipulators

Today’s money tricksters, however, remain unaccountable. Some of them enjoy high prestige and still have their pensions to look forward to: Nixon, Bernanke, Yellen, Powell, Draghi, Lagarde. Just as these officials put themselves in the limelight with vulgar “scientific” speeches, they should then also be liable by name when things go wrong. They stand in the vast gallery of all-time money manipulators.

Not only have they made the rich richer through immeasurable money creation, while making savers and their pension funds poorer; not only have they offered politicians the printing press for all of their insane expenditures, but they built up the “doom-loop” that ties all monetary institutions, the state, paper values, and the euro on the same side of the scale and threatens the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people.

That the economy can only run with high monetary liquidity, as John Law or later John M. Keynes assumed, is a fairy tale. The entire industrial revolution up to 1914 took place under the gold standard. Every bank bill could be exchanged for gold over the counter. Money was scarce and prices often fell for decades, for example from 1873 to 1896. This made consumers richer, rewarded savers and those who built capital, and it punished debtors. The fact that capital markets in France at that time—and after the 2008 financial crisis—were empty is not due to too little money or too little liquidity, but to government deficits that soak up capital and prevent productive, wealth-creating use of it.

Translated from German by Thomas and Kira Howes

Further Reading

James Buchan, John Law. A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century. London: Maclehose Press, 2018.

John Law, in: New World Encyclopedia, Dez. 2020 https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Law_(economist)

Claude Cueni, Das große Spiel. Munich: Heyne, 2006 (a novel, but a faithful telling).