Many lost their jobs during the Coronavirus pandemic, especially in the USA, while many jobs were saved in Europe. In any case, the crisis has something to teach policymakers. (Image: realinemedia/Shotshop.com)

Many lost their jobs during the Coronavirus pandemic, especially in the USA, while many jobs were saved in Europe. In any case, the crisis has something to teach policymakers. (Image: realinemedia/Shotshop.com) The Covid 19 crisis threw many out of work, and many suffered accordingly, but labor markets were also damaged. Depending on the situation, governments made it worse—or better. It turns out labor markets require proper care, and politicians can learn a few things from the pandemic.

Companies in Central Europe are calling their workforces back to familiar workplaces…In the U.S., on the other hand, the labor market has crumbled, with companies scrambling to find employees they can't find anywhere.

For once, timid Central Europe got it right, while the usually nimble, flexible Americans got it wrong. In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, governments immediately implemented the tried and tested instrument of short-time work. Companies that ran out of orders or were shut down because of the virus usually continued to pay wages, but were reimbursed sixty, seventy, or eighty percent of the costs by authorities. The offices were familiar to them, the procedures were well-rehearsed and, most importantly, the workforces were not laid off. All short-time workers stayed connected to their company. To a lesser extent, France and Italy were also familiar with short-time work, although in Italy the Cassa Integrazione kept the overwritten workforces further away from their company.

The situation was quite different in the USA. In the first months of the crisis in 2020 around twenty-two million workers were put on the street. They received unemployment benefits from the individual states, then also from the federal government, but they were out of work. In contrast to Central Europe and Scandinavia, the U.S. does not have an “activating unemployment policy,” while in Germany, Austria and Switzerland much is done for job placement, retraining and continuing education.

The European variant protects individuals and their households, and does not allow their consumption to collapse completely, which has a better effect in crises than the American average between income and unemployment.

Central Europe and the USA: Two Different Labor Market Worlds

It is now apparent that there were entirely different consequences for these countries, even as we emerge from the viral crisis: Companies in Central Europe are calling their workforces back to familiar workplaces. The workers know the processes, everything goes from zero to hundred within a short period of time, just like in car commercials.

In the U.S., on the other hand, the labor market has crumbled, with companies scrambling to find employees they can’t find anywhere. There is a shortage of truck drivers, construction workers, salesmen and saleswomen. There are also yawning gaps in the service professions, with former employees everywhere refusing to rejoin the workforce, or at least to trade in the comfort of their home offices for their jobs and commutes. Along with the labor market, some supply chains are also disintegrating; there are shortages in the supply of components, even on store shelves.

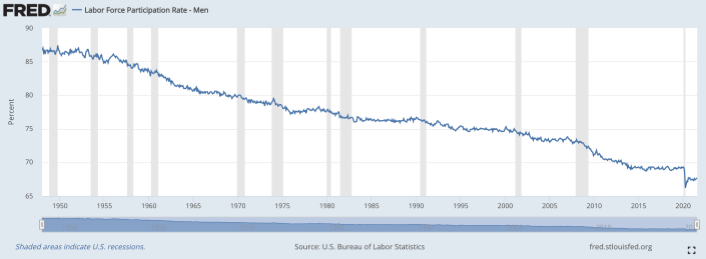

The first statistical signs of alarm are apparent—in the USA, the labor force participation rate, i.e., the percentage of those capable of working who are working, has probably fallen even further, below 63%. In Switzerland, it is 83%—which means that in the U.S., two active people must carry a non-working person privately or with social assistance, but in Switzerland, five active people need to carry an inactive person. That’s worlds of difference in costs. It is even worse in Italy, where only 58% work, and in Spain where it is 60%. Accordingly, Italy’s national product fell by 7.5%, in Spain by 6.4%, in France by 3.4%, but in Germany and Central Europe only by a tiny bit. As employment fell so did contributions to the social security systems of these countries, including the United States.

Coronavirus Aid Packages without End and Skyrocketing Government Deficits

No wonder government deficits skyrocketed, along with the tens of billions in aid packages that went directly to corporations. These enormous deficits also create unbridgeable financial holes for the post-crisis period. The debts of France and the U.S. are now reaching a percentage in terms of national product that triggered the euro crisis in Italy in 2010. This time, however, everything is “covered” by the freshly printed money of the central banks—which simply postpones the crises for another day.

In terms of the labor market, another crisis payment, also issued in Italy, has a disconcerting effect: unconditional money for citizens. In the U.S., President Biden’s first package gave all adults $1400 up to a couple’s income of $150,000, i.e., up to the upper middle class. Further, massively increased child tax credits were promised, and the unemployed everywhere will have their national funds topped by Washington without any further proof.

In Italy, the “reddito di cittadinanza,” a citizen’s income between 480 and 9360 euros a year, has already been paid out since 2019 to 1.6 million needy people who have persevered but have been dismissed from the national economy and forgotten. And everywhere, labor force participation fell dramatically. In the United States, cumulative direct payments to the unemployed often exceeded the wages of the unskilled. So why work?

Whether or not, as proponents of basic income claim, everyone will instead be active in the arts or in volunteer work is more than doubtful. It is no simplification to say that this suggests to citizens—and voters—that income from the state is possible without preconditions and is easily provided by the money presses. Moreover, this dries up the labor market—and ever fewer active people must pay for those who are idle. Thus, the foundation of the economy erodes.

Incidentally, America could have used the Earned Income Tax Credit, the aid for the working poor, if it wanted to dip into the coffers. This aid automatically adds 40% to small partial incomes, and slowly reduces it after about $18,000 in total income—but of every dollar earned above that, the low-wage earner is left with 79% in his pocket. This encourages people to work, but the unsolicited lump sum payments lower the will to work and drain the labor market. This also hurts companies—FedEx just complained that unavailable workers cost them $450 million last quarter.

Benefits of the U.S. Labor Market for Productivity and Innovation?

But could the U.S. hire-and-fire system also have benefits? Relieved of their previous workforces, firms are now rebuilding themselves, often radically. They are eliminating unprofitable jobs, and they are moving into other sectors with new recruits. Workers are joining in—according to surveys, half of all employees want to do something different in the next two years. For their part, two-thirds of the unemployed are no longer looking for a job in their current line of work. The U.S. labor market is thus turning at a rapid rate.

This may boost productivity much faster than in Europe, where barriers to layoffs prevent this rapid turnover in the labor market. But this turnover points to a weakness of the American economy—it has many low-skilled jobs in trade, mail-order companies, and fast food, and fewer high-precision manufacturing firms with necessarily stable, educated workforces in mechanics, machinery, and appliances as you have in Germany, Austria, Switzerland. Such products are imported and cause a large trade deficit. For the past fifty years, that too has been paid for with freely printed dollars.

Still, another plus point of the U.S. labor market, this time in favor of those getting back into jobs—wages are exploding in some places, with companies in desperate need. Even retailers like Amazon, notoriously criticized, are outbidding the minimum wage by 20%, and not for bankers or IT specialists (for them, too), but for the aforementioned armies of unskilled workers.

Conclusion: Supplement “Labor Market Care” with Liberal Termination Rights

nly a preliminary conclusion remains: the jury is out. Nothing is yet clear about the future path of the USA and Europe in terms of productivity, wage movement, full employment, or prosperity. Nevertheless—the European way is less adventurous and stresses the working people less. But it could enjoy both advantages if, as in Denmark and Switzerland, the cautious “labor market care” were supplemented by greatly facilitated layoffs in normal times. Then there would be faster success with the turnover of the workforces and its corresponding advance in productivity, all without sending the workers unaccompanied and into the void. As is well known, Denmark and Switzerland are fully employed and prosperous—precisely thanks to the right to dismiss. Companies hire more when they are allowed to cut back. Elementary, my dear Watson.

Europe could have the best of both worlds.

Translated from German by Thomas and Kira Howes