Cluttered cables over Bolivia’s capital La Paz: At first glance, the statistics put Morales’ term of office in a good light. But the “socialism of the 21st century” turned out to be a mixture of authoritarianism and corruption. (Picture: pixabay)

Cluttered cables over Bolivia’s capital La Paz: At first glance, the statistics put Morales’ term of office in a good light. But the “socialism of the 21st century” turned out to be a mixture of authoritarianism and corruption. (Picture: pixabay) For a long time, Bolivia was hailed as the successful example of so-called 21st century socialism. While countries like Venezuela and Nicaragua were in a major socio-political and economic crisis, the Bolivian economy was booming, impressing economists and politicians from all over the world. International media compared Evo Morales to politicians like Bernie Sanders and reported on the success of the Bolivian model.

Morales’ victory in the 2005 elections is a milestone in Bolivian history. With 56% of the votes, Morales became the first president of the post-dictatorship era to win more than half. But more importantly, in a country where half the population self-identifies as indigenous, he was the first indigenous president. With his revolutionary tone directed at the indigenous people, Morales, a former coca farmer, won the votes of that community which had until then been kept away from the country’s politics and power structure.

The Nationwide Protest against Morales Has Surprised the International Community

At first glance, the statistics seem to show Morales’s 14-year mandate in a positive light: Inequality (measured by the GINI coefficient) fell from 56.7 points in 2005 to 42.2 in 2018; the illiteracy rate halved between 2006 and 2015 (from 14% to about 7% of the population); the gross domestic product grew steadily—Bolivia was thus one of the fastest growing countries in South America—; and, in 2014, 48% of parliamentarians were women, many of them indigenous.

For countless people in Bolivia, the approaching end of the Morales regime was a first glimmer of hope after all these years of state socialism.

It is therefore not surprising that the international community was surprised, even stunned, when in 2019 an estimated three and a half million Bolivians—almost a third of the population—took to the streets to demand Morales’s resignation. Meanwhile, for countless people in Bolivia, the approaching end of the Morales regime was a first glimmer of hope after years of state socialism marked by the constant suppression of fundamental freedoms, the gradual introduction of an authoritarian government, the politicization of institutions, corruption, and absurdly high public spending. A deeper analysis of these years shows that Morales’s alleged successes were fragile and could not be sustained in the long term.

The Bolivian population is very heterogeneous. The constitution recognizes 38 different indigenous population groups, in addition to Mestizo and white. Although universal suffrage was introduced as a result of the “Revolución Boliviana” in 1952—the only revolution in Latin America publicly supported by the U.S.— for decades the political power remained in the hands of a small white elite (even if no dictatorship ruled the country at that time). The rights and needs of the indigenous people were often ignored. Corruption and mercantilism were part of everyday political life, and political and economic decisions were often made under pressure from the U.S. government.

From State Capitalism to the “Neoliberal Era”

After the revolution, Bolivia experienced its first period of state capitalism. This period, characterized by state mismanagement, ended abruptly 33 years later with one of the highest inflation rates in history. Between May 1985 and August 1985, the annual inflation rate reached 60,000%. After a change of government, hyperinflation was stopped in just ten days, and a new economic course followed over the next three years. The political system and economic structure underwent profound changes. After the failure of state capitalism, it quickly became clear that Bolivia had to open its economy to an increasingly globalized world. State corporations were partially or even completely privatized. The most important of these, YPFB, an oil and gas company, continues to generate a large part of the government’s revenues to this day.

In addition, prices of goods, interest rates and exchange rates were no longer set by bureaucratic institutions but were freely determined by economic signals. The role of the state in the economy was limited, and Bolivia was again able to attract foreign investment. The heyday of what is now known as the “neoliberal era” lasted until 2002. The decisions taken at that time favored economic development, but the political elite did not succeed in easing the social and political tensions that accompanied it. The growing resistance of the indigenous population put the political system under renewed pressure, and the old parties lost credibility.

After the so-called Guerra del Gas, which resulted in 60 deaths, President Sánchez de Lozada resigned in 2003 and fled to the U.S. His vice-president Carlos Mesa succeeded him, but the conflicts did not end there. To calm down the demonstrators, Mesa also decided to resign in 2005. All his constitutional deputies resigned with him, which meant that Rodríguez Veltzé, the Chief Justice of the Bolivian Supreme Court, had to serve as interim president. He called new elections to be held in December 2005.

Morales’s election campaign was characterized by anti-American and anti-capitalist positions.

Evo Morales, who was already an elected official, played a leading role during the protests and announced his intention to run for the presidency. His election campaign was characterized by anti-American and anti-capitalist positions. He promised an immediate end to cooperation with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the nationalization of major corporations, and greater involvement of indigenous peoples.

The Gradual End of Private Enterprise

In December 2005, Morales was elected with a healthy margin-of-victory. One of his first actions was to nationalize the oil and gas company YPFB, as he had promised on the campaign trail. This was followed by the nationalization of thirteen other companies. After almost twenty years, Bolivia’s economy returned to a system of Keynesian state socialism similar to that of the period between 1952 and 1985. Thanks to the strategic nationalization of mining, natural gas, and oil companies, as well as the simultaneous rise in the price of these commodities on the world market, the Bolivian state suddenly had higher revenues than in previous years.

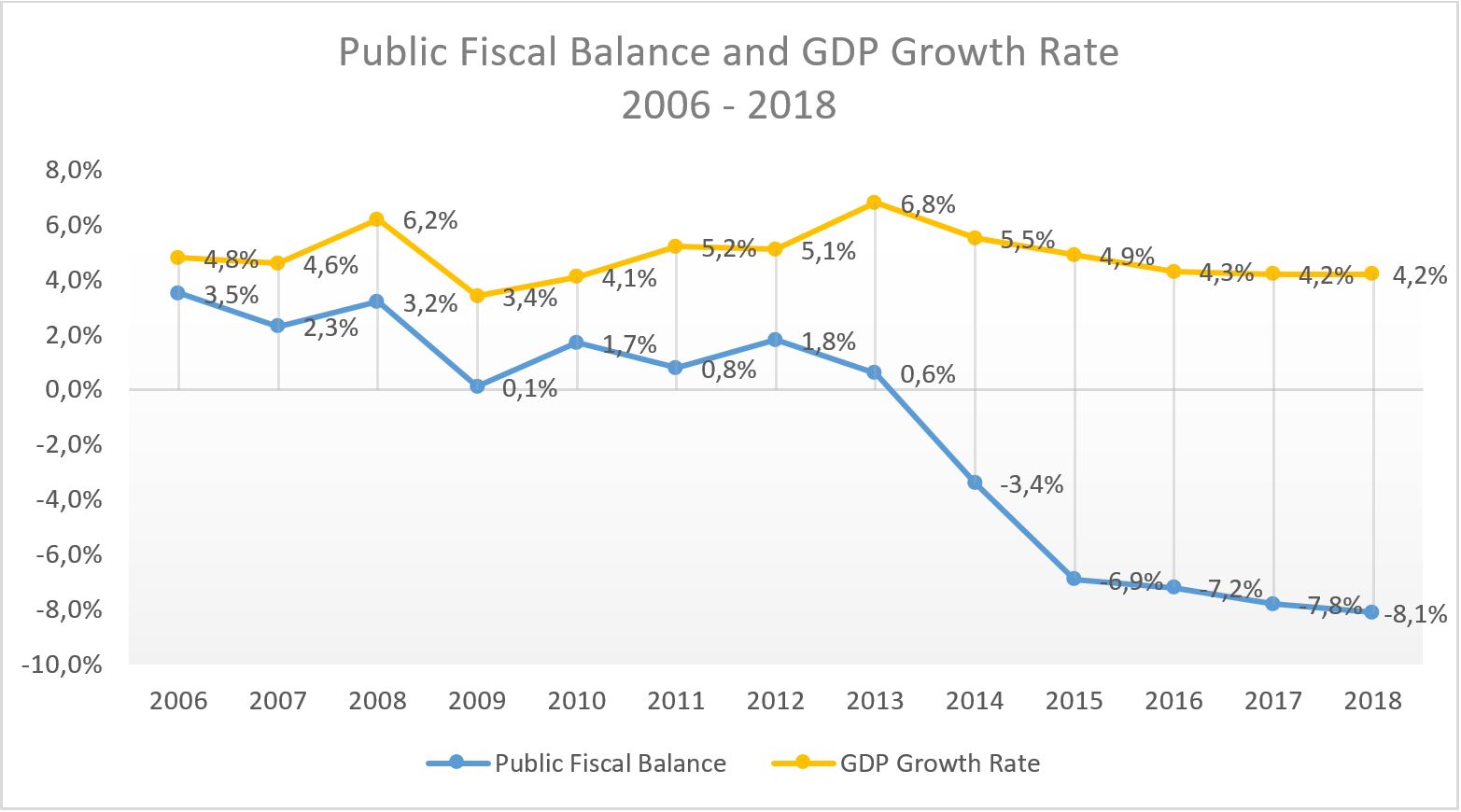

Between 2006 and 2016, the Bolivian state had revenues of around 33 billion U.S. dollars from the export of natural gas. Between 2006 and 2013 the state had an average annual surplus of 1.7%. These surpluses were invested in state enterprises. In 2017, 36 companies—many of them newly founded—were state-owned. Public investment increased six-fold over fifteen years, with the 2019 budget allocating approximately $11 billion to the maintenance of state-owned enterprises, $415 million of which was spent on salaries alone. But the problems of inefficient bureaucracy and mismanagement were not far behind, and companies like Quipus—which produces laptops and mobile phones “Made in Bolivia”—could obviously not keep up with international competition.

However, the state allowed such companies to continue producing. During this period alone, eight state businesses became insolvent; in 2019, the (still) living companies had revenues of 7 billion USD, compared with expenditures of 7.8 billion USD. These zombie companies brought further problems for the economy: Since they did not have to show any profit, there was a distortion of competition compared to private companies that could not offer their services and products below production value in the long run. Thanks to the non-existent competition, several private businesses, especially in the dairy and paper products industries, as well as several airlines, filed for bankruptcy.

After commodity prices fell in 2013, the Bolivian economy could no longer ignore reality. Years of failed economic diversification and deterring private investors had a negative effect on the Bolivian economy. To keep the GDP growth rate constant as a political measure — despite a growing budget deficit, the government decided to increase its debt. Since 2006, foreign debt has almost quadrupled, and by 2019 it had reached a level of 11 billion USD, a historic high. Between 2006 and 2014, the domestic debt of the Banco Central de Bolivia (BCB) increased by 1.102%, by 2019 it had already reached 4.8 billion U.S. dollars. The central bank’s foreign exchange reserves stood at 15 billion USD in 2015, and three years later this number had shrunk to 9 billion USD. The artificial boom disappeared, and the average budget deficits of the past three years exceeded the steady surpluses of the eight previous years. This system requires that the state take on new debts every year to keep the economy running.

But these were not the only economic policy mistakes of those years. The burdensome bureaucratic hurdles and relatively high taxes meant that many micro and small businesses were unable to be registered in accordance with the law. Even according to the government, 77 out of 100 Bolivians work in the so-called informal sector without paying social security contributions, i.e. without any entitlement to worker’s compensation or severance pay. According to the Index of Economic Freedom of the U.S.-based Heritage Foundation, the Bolivian economy is one of the least free in the world as a result of state repression. In the ranking of economic freedom, it ranks 175th out of 180 nations, only higher than Cuba and Venezuela among Latin American countries. It does not pay to be an entrepreneur in Bolivia.

The Failure of “21st Century Socialism”

State control was not limited to the economy. To contain criticism of his government, Morales increasingly curtailed the civil liberties of Bolivians. In 2019, the World Press Freedom Index ranked Bolivia 113th in terms of press freedom and state censorship. Since 2011, the Human Freedom Index of the Cato Institute and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom shows a decreasing trend in freedom for Bolivia (ranked 97th out of 162 analyzed countries). Opposition politicians were systematically persecuted. Many had to flee the country, and others ended up in prison. The political tension divided the country, and the more productive and richer departamentos in the east of the country became bastions of the opposition. The departamentos in the west, underdeveloped and with an indigenous majority, became the base of Morales’s party. Morales’s popular slogans left deep divisions in Bolivian society, and discrimination between citizens from the West and East became part of everyday life.

In 2009 Morales was re-elected with 64% of the vote. He ran for a third term in 2014, even though the Constitution limits his term of office to two legislative periods. However, a new constitution was adopted in 2009, and Morales argued that he had only served one term under the new constitution and was therefore entitled to run for a third time. He won the election with 61% of the vote. After three terms in office, Morales decided to call a constitutional referendum in 2016, trying to lift the term limit. To Morales’s surprise, the amendment was rejected by the electorate—six of the nine departamentos voted against it. This was the first time Morales had lost a national election. But since he had all state institutions under his control, the Supreme Court decided in 2017 to abolish the term limit restriction. The court based its decision on the American Convention on Human Rights. This allowed Morales to run for a fourth term in 2019.

Statues of Morales and former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez were destroyed.

The years following the referendum were overshadowed by corruption scandals. The deterioration of the economy also weakened Morales’s influence. The elections in October 2019 turned into a scandal: The Supreme Election Review Commission stopped publishing the election results when only 80% of the votes had been counted, and a run-off between Morales and former President Mesa loomed on the horizon. Two days later, the Court announced the final result: Morales had won the first round. The people complained about several irregularities during the count and accused Morales of election fraud. The Bolivians took to the streets, and the country was paralyzed for weeks. The Organization of American States (OAS), which had taken a pro-Morales position in the past, decided to conduct an audit while millions of people protested in all nine departamentos.

The OAS published the audit, which confirmed that the vote count had many ambiguities and that electoral fraud was very likely. The digital magazine Republik published a detailed article about the events that transpired after the election. The police, who had previously suppressed the demonstrators by force, now refused to do so. Morales finally gave in to the demand for his resignation on November 10th and immediately fled to Mexico. After 19 days of protests, the Bolivians celebrated Morales’s resignation. Statues of Morales and former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez, who had also paid homage to socialist ideas, were destroyed.

A transitional government of experts and opposition politicians took power and has been preparing new elections ever since. After 14 years of growing oppression, a young generation that had experienced no other president than Morales recognized the misery of socialism and decided to fight for a freer future. It remains to be seen whether the elections will bring a meaningful change of direction. But one thing is clear: “Generation Evo” has had enough of 21st century socialism.

As part of its educational offering and as an investment in the future, the Austrian Institute supports and promotes particularly talented young authors, such as the author of this article, by giving them the opportunity to publish. As with all other contributions, we always pay attention to quality in terms of both style and content.

Translated from German by Thomas and Kira Howes.