A young man holds a sign reading “We are the 99%” at an Occupy Wall Street demonstration, spreading the anti-capitalist narrative that the super-rich are leaving the rest of the population behind and enriching themselves at their expense. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

A young man holds a sign reading “We are the 99%” at an Occupy Wall Street demonstration, spreading the anti-capitalist narrative that the super-rich are leaving the rest of the population behind and enriching themselves at their expense. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The parallel is intentional, the title a provocation: with his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Frenchman Thomas Piketty alluded to Karl Marx’s magnum opus Das Kapital. And with it, Piketty struck a nerve. Alongside his co-authors Emmanuel Saez and later Gabriel Zucman, he inspired the “Occupy Wall Street” movement, which mobilized with its slogan “We are the 99%” against an alleged new oligarchy of the rich.

The fact that the gap between rich and poor is constantly widening—not only in the USA, but everywhere in the industrialized countries—became a commonplace claim and was no longer questioned.

The research of these three French scholars shook the USA. In the Democratic Party, Piketty’s work triggered calls for higher taxes for the rich and a hefty wealth tax.

The Demise of the Three Musketeers: Misinterpreted Tax Data

Based on Piketty’s research, the magazine The Economist also stated in 2006: “The one truly continuous trend over the past 25 years has been towards greater concentration of income at the very top.” The fact that the gap between rich and poor is constantly widening—not only in the USA, but everywhere in the industrialized countries—became a commonplace claim and was no longer questioned.

But there has begun a demystification of the “three musketeers,” as the French scholars are sometimes reverently called. The two authors Gerald Auten and David Splinter have contributed significantly to this with an article in the Journal of Political Economy, a leading specialist journal. Auten works in the US Department of Finance, Splinter in a congressional committee that deals with tax issues. Their work also appears to be trustworthy because they have had access to the results of tax audits.

Little Remains of the Rising Inequality: The Top 1 Percent Has Barely Increased

Taxes and Transfers Change the Picture

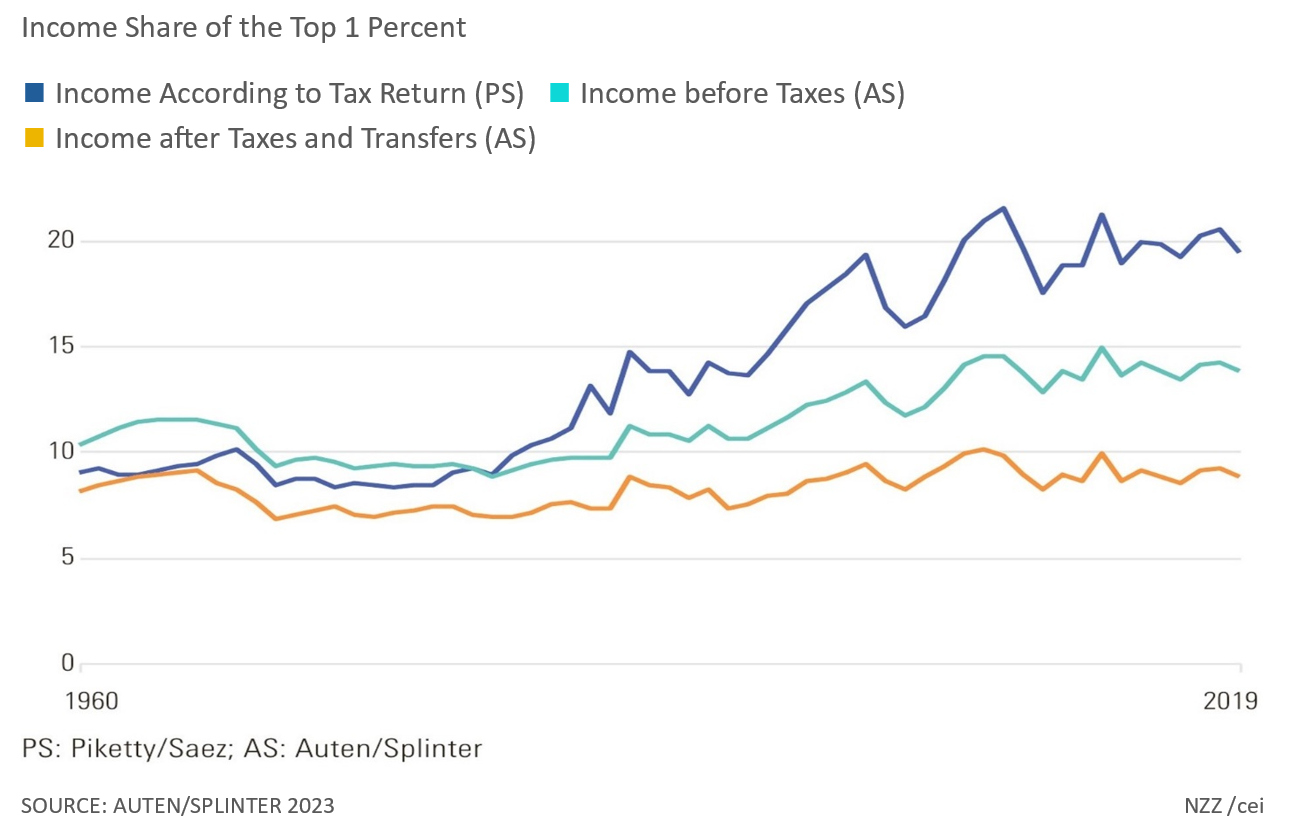

The main finding of Piketty and his colleagues, which has resonated so much internationally, is that the richest one percent more than doubled its share of total income from 9 percent in 1962 to 19 percent in 2019. This does not include taxes and transfers. In contrast, the share reported by Auten and Splinter only rose slightly from 11% to 14%. There are several reasons behind this discrepancy:

- A third of Piketty’s increase is the result of a tax reform in 1987, when the top tax rate in the USA was reduced from 50 to 28 percent. Before 1987, rich Americans therefore often left profits in their companies, after 1987, they increasingly had them distributed, and this meant that they appeared on their tax returns. They did not become richer as a result. Auten and Splinter ensure that the measured inequality also corresponds to real inequality.

- In 1960, 67% of tax returns were completed by couples, but by 2019 this proportion had fallen to 37%. In contrast, the proportion of married couples in the top one percent remained almost constant at 85%. At the bottom of the distribution, there are therefore many more tax brackets with low incomes. By contrast, the incomes of rich tax brackets remained high because they tend to comprise two people rather than just one. Auten and Splinter therefore base their income classes on individuals rather than tax brackets. This reduces the share of the richest one percent.

- Around 40 percent of national income does not appear on individual tax returns. In the USA, this includes health insurance, for example, which is taken out via the employer. This is a wage component that is not taxed.

Auten and Splinter address this and other distortions in Piketty’s original work. For example, using tax audits, they found that 15 percent of unreported corporate income should be attributed to the top one percent. In a more recent paper, however, Piketty assigned half to the top one percent, which overstates their income.

The Astonishing Constancy of Income Inequality

In the much-cited study by Piketty and Saez, taxes and transfers play no role. If both are taken into account, the share of the top one percent of income after redistribution has remained almost constant at 10 percent since 1960. This result by Auten and Splinter is spectacular, precisely because Piketty’s narrative, according to which inequality is constantly reaching new highs, has dominated reporting for two decades.

This constancy may seem surprising at first glance, as the highest marginal tax rate fell from 91% to 37% during this period—so you might think that redistribution in the USA has decreased. However, the highest tax rate in 1960 did not affect more than 500 households. Despite falling tax rates, the average tax burden on the richest one percent climbed slightly from 38 to 42 percent because the tax base was expanded at the same time. The tax burden on the bottom 80 percent, on the other hand, fell sharply, especially since the turn of the century.

Not to forget, people on low incomes are also increasingly benefiting from government transfers. Their share of US economic output has increased from 5 to 16 percent in 50 years. On the one hand, a large proportion of the baby boomers have now retired. On the other hand, health insurance for the retired (Medicare) and for poor households (Medicaid) has been greatly expanded.

The middle class and poorer households have therefore received tax relief in recent decades, while at the same time transfers have increased significantly. Together, these two factors have helped to ensure that the somewhat greater concentration of market income among the top one percent has been practically offset by redistribution. The welfare state in the USA therefore has a balancing effect.

Half of Americans Left Behind? Ideology instead of the Search for Truth

Piketty’s view is different. A few years ago, he commented on his research that half of Americans had been left behind because they had failed to share in the economic gains.

However, this statement is by no means confirmed by Auten and Splinter. According to their study, the per capita income of the bottom 50 percent (after taxes and transfers) tripled in real terms from $10,000 to $30,000 between 1960 and 2019. A good portion of this comes from increased government transfers and tax breaks, but even without these, income would still have doubled.

The study by Auten and Splinter is certainly a step forward. Nobel Prize winner James Heckman recently told The Economist that Piketty’s work was careless and politically motivated. Although the French scholar has refined his results over the years, he has stuck to his basic conclusions.

However, it is to be feared that the new research will never become as well known as the alarmist statements made by Piketty and his colleagues. They reacted to the criticism with little aplomb, accusing their opponents of spreading a lie of inequality (alluding to the “climate deniers”). One gets the impression that Piketty and his colleagues are more committed to ideology than to the search for truth.

This article originally appeared in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on January 4, 2024, p. 25, and online at nzz.ch. With kind permission.

Translated from German by Thomas and Kira Howes

On this topic, see also:

Phil Gramm, Robert Ekelund, John Early: The Myth of American Inequality. How Government Biases Debate Policy. Roman & Littlefield, Lanham-Boulder-New York-London 2022 (The authors mention earlier calculations by Auten and Splinten).

You can download the aforementioned article by Gerald Auten and David Splinter in the Journal of Political Economy: download here.