"Stakeholder capitalism" or, as critics say, "stakeholderism": can it translate its noble goals into reality or does it only serve managers and their interests? (Image: Faithie/Shotshop.com)

"Stakeholder capitalism" or, as critics say, "stakeholderism": can it translate its noble goals into reality or does it only serve managers and their interests? (Image: Faithie/Shotshop.com)

A better economy is possible. Speaking in broad and general terms, it is difficult not to agree with the title of Klaus Schwab’s essay recently published in Time Magazine. For there is nothing in human affairs that cannot be improved. Companies and financial firms can be improved, and the rules that govern the market economy can certainly be improved.

What Does a “Better” Economy Mean?

The problem, of course, lies in the meaning we give to the word “better.” Schwab sees the solution in what he calls “stakeholder capitalism.” This term was not coined by the founder of the World Economic Forum. For years, there has been much discussion about the importance of stakeholders. These stakeholder groups are linked to a company by various interests, interests that they usually assert at the expense of the shareholders.

According to Schwab, for “the past 30 to 50 years”—and it would be interesting to know whether it is actually thirty or fifty years—“the neoliberal ideology has increasingly prevailed in large parts of the world. This approach centers on the notion that the market knows best, that the ‘business of business is business,’ and that government should refrain from setting clear rules for the functioning of markets. Those dogmatic beliefs have proved wrong.” Schwab writes this as if it were something new, when in fact this has long been mainstream in published opinion—it is a new kind of dogmatism that is sweeping the media and politics.

Accordingly, to free themselves from the effects of “narrow and short-term self-interest” and create a “more inclusive and sustainable model,” companies must move away from purely economic calculations. According to Schwab, their performance should be measured not only by profits, but also by “nonfinancial metrics and disclosures” added to annual reports “making it possible to measure their progress over time.”

What Should the State Do—And What Shouldn’t It Do?

Rethinking the capitalist system has not necessarily become more urgent because of the pandemic. But it has undoubtedly become easier, and the temptation all the greater, to challenge the status quo because of the growing importance that governments have gained, or at least conceded to themselves, a little bit everywhere.

Today, more than ever, it is the state that clearly has the upper hand. Governments are actively working to compensate private companies affected by the shock of the pandemic. But some clarification is needed here. This shock has more to do with political containment measures than with the natural occurrence of a virus itself. These measures have severely compromised social exchange and, by extension, economic exchange.

The pandemic is the golden opportunity to attach new government conditions to corporate support or, more generally, to steer public action in certain directions.

But instead of seeing these compensations as an expression of the fact that the state is, so to speak, a kind of collective insurance, that is, that its very function is precisely to cushion such an extraordinary damaging event, they are the pretext for ever more far-reaching political interventions. For some, the pandemic is the golden opportunity to attach new government conditions to corporate support or, more generally, to steer public action in certain directions.

European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde said in an interview that the central bank, which has become the lender of last resort for the entire continent, holds about 20 percent of the green bond market. So, is this what issuing institutions need to do to create “better capitalism”? They invest in possibly unprofitable business and in return forego their statutory tasks, i.e., the targeting of a certain level of inflation, and thus the stability and security of national economies?

Behind Schwab’s lofty words lies a Machiavellian logic: the end justifies the means. A particularly lofty end also justifies foregoing the elementary rules of the market system. But at what price?

The Social Dimension of Profit

Despite widespread rhetoric to the contrary, we already live in a world that has little to do with the business of business being business. Various forms of sustainability and social responsibility have long been the norm in all major corporations, which produce and report detailed social balance sheets on a non-stop basis. You don’t need to go to Davos to know that nowadays a company’s employees and the various countries in which it operates are already special “stakeholders,” i.e., entitlement and interest groups.

However, the fact that a company makes a profit is the best guarantee that workers will be paid fairly and may even see their wages rise. A profit-oriented company also has the means to take care of the social concerns of the environment in which it operates. As a reminder, therefore, in the tumultuous years of early industrial capitalism, great capitalists voluntarily looked after their community. They established schools and hospitals for their workers, for example, for which they were criticised as paternalists. How times have changed.

According to Schwab, however, the “better capitalism” should now be the one in which vague parameters such as social justice and corporate social responsibility are given the same importance as the company’s balance sheet. That is to say, they become an instrument for evaluating the actions—i.e. the business success—of leading managers.

Is that really desirable? Understanding what people’s needs are, what to produce, under what conditions and where, is anything but an easy task. Production decisions are the result of a whole series of assumptions, risks, and considerations of competent businessmen. Some turn out to be right, others wrong; the success of individual careers and even entire companies depends on them.

And yes, it is true: Some entrepreneurs and business leaders are sometimes right “too early,”: that is, at a time before a technology becomes profitable. That happens; it is one of the risks that private actors bear. Time is everything in business: The fact that a particular product does not make a profit does not imply any judgment on the human or professional qualities of those who worked on it. It only means that the same means of production can be used differently and better for the benefit of society as a whole.

The New Managerial Class

Critics of the market system condemn the profit motive, as if anyone on this earth would really claim that profit is the only thing that drives people. Even the darkest anthropology would never devise such a claim. In truth, profit is nothing more and nothing less than a “signal.” It shows that the calculations work out, that a product is more profitable than it costs to produce it, because it satisfies a consumer need, because it contributes to the best possible use of scarce resources.

What would happen if managers could truly say that they were operating not for the benefit of their shareholders, but in the name of a higher ideal?

Profit is also a yardstick for evaluation. Thanks to it, the shareholders can measure the actions of managers (who know the company much better than they do). Having to make a profit, having a clear goal, allows the owners of a company to evaluate performance. We know that this is never easy. Scandals and frauds remind us of this every day. But what would happen if managers could truly say that they were operating not for the benefit of their shareholders, but in the name of a higher ideal (whatever that ideal might be)?

Why should non-financial benchmarks be for the benefit of society as a whole? It is far from clear. If a company is making a profit, it is more likely that it will be able to maintain employment levels, constantly renew its technologies, and thus keep its effects on the environment low. But if a CEO can claim, with the best reasons in the world, to give up some of his profits in the name of a desirable social cause, who can be sure that this is true?

The “Better Capitalism” Is Primarily a More Manager-Friendly Capitalism

In reality, Schwab’s “better capitalism” is primarily a more manager-friendly capitalism. I mean CEOS and executives like those attending the Davos meeting who, like all of us, want to have as free a hand as possible in their decisions without having to bear the responsibility.

According to the management consulting firm Georgeson, companies in Italy, Spain and Denmark cut dividends during the Coronavirus crisis (by 44, 51, and 28 percent, respectively). But only 29 percent of companies in the first two countries (and no Danish companies) trimmed their managers’ pay. In other words, some companies in these three countries have preferred to burden investors while not touching their managers’ compensation.

The problem for companies, as for all other institutions, is to avoid self-referencing and to be as transparent as possible. According to Schwab, improvable, responsible capitalism is arbitrary capitalism in the hands of managers. It is therefore PR in the service of a caste. This is not in the interests of society. For companies should not become mere temporary tools in the hands and for the benefit of their managers.

Therefore, like it or not, anyone who wants to stop this change, already underway, should really think in terms of profit or gain. Those who, on the other hand, want to give managers a free hand for their arbitrary rule should definitely promote Klaus Schwab’s PR idea.

This article first appeared under the title “Der angeblich bessere Kapitalismus” in the Neuen Zürcher Zeitung on 1.15.2021, p. 30, online: “Der bessere Kapitalismus ist der schlechtere Kapitalismus—warum die neuen Vorschläge von WEF-Gründer Klaus Schwab et al. bloss die Managerkaste begünstigen.” Published with kind permission.

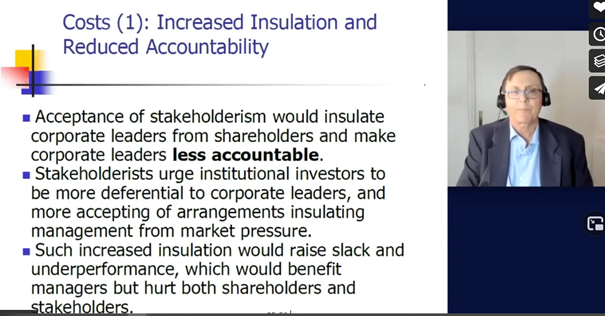

Klaus Schwab responded to Mingardi’s article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung the day after it appeared. Among other things, he accused Mingardi of not having understood the idea of stakeholder capitalism and of arguing in an unscientific manner. However, Mingardi’s analysis is largely consistent with that of Harvard professor Lucian A. Bebchuk, as he recently presented it in a controversial discussion recorded on Vimeo with Alex Edmans, professor at the London School of Economics. Bebchuk pointed out—based on empirical findings,

- that acceptance of “stakeholderism” he criticized would insulate corporate leaders from shareholders and make corporate leader less accountable;

- that, second, that stakeholderists urge institutional investors to be more deferential to corporate leaders, and more accepting of arrangements insulating management from market pressure;

- and that, third, such increased insulation would raise slack and underperformance, which would benefit managers but hurt both shareholders and stakeholders.

Here is a screenshot of the corresponding slide of Professor Bebchuk’s presentation:

Bebchuk therefore argues that the legitimate interests of stakeholders can be protected or promoted in an efficient manner only through legal regulation in the relevant areas.

See also:

- Lucian A. Bebchuk, Roberto Tallarita: The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance.

- Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, Roberto Tallarita: For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain