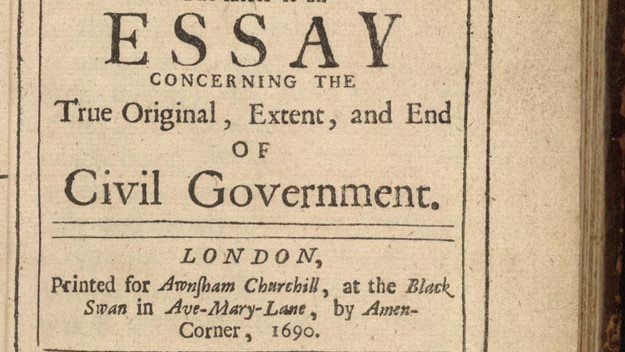

Did the classics of liberalism misunderstand freedom? Lower section of the title page of John Locke's "Two Treateses on Government", published in 1689 (Picture: Wikimedia Commons)

Did the classics of liberalism misunderstand freedom? Lower section of the title page of John Locke's "Two Treateses on Government", published in 1689 (Picture: Wikimedia Commons)

Last June, the liberal Schweizer Monat called Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed the “Book of the Hour.”[1] The internationally discussed work of a political scientist who teaches at the renowned Notre Dame University—a book that would also be published in German in 2019—was reviewed in the New York Times (twice[2]), The Economist,[3] and the Wall Street Journal.[4] Although he disagreed with most of its conclusions, former President Barack Obama also praised Deneen’s reckoning with liberalism on Facebook for its “cogent insights into the loss of meaning and community that many in the West feel, issues that liberal democracies ignore at their own peril..”[5]

The more left-wing Austrian radio station ORF1 granted the author a friendly fifty-minute interview in which the Catholic communitarian, who is decidedly critical of free markets and globalization, praised European social democracy (at the instigation of the moderator) as the force that had countered the violence of “raw, unbridled capitalism” and untamed markets. If by “social democracy” one understands a “moderate market economy” that ensures that social welfare is provided for and social goals are pursued, then, Deneen told ORF1, we should consider how social democracy could be strengthened in America.[6] Deneen explained—without being contradicted by the moderator—that the “architects of European social democracy were mostly Catholics.” It is reasonable to assume, then, that he has a confused understanding of recent European history.

This article has been originally written in German and is also available as PDF both in German and in English. (Austrian Isntitute Paper 35 and 35-EN, respectively).

DOWNLOAD PDF in English / DOWNLOAD PDF in German

For a short version, that was published in the Swiss journal “Neue Zürcher Zeitung,” click here.

“Liberalism Is a Victim of Its Own Success”

Even if it repeats some well-known positions, such as those of Alan Bloom (The Closing of the American Mind) and Alasdair MacIntyre (After Virtue), the book is a challenge for every liberal, but especially for the Catholic liberal because of the author’s position. After all, Deneen also puts his finger on sensitive issues of modern society and brings up topics that liberals like to sweep under the rug—often self-righteously and arrogantly. This is how Alexander Grau summarizes it in the Schweizer Monat: “Deneen exposes the aporias of liberal ideology and shows how liberalism produces with a fateful logic homogeneity, authoritarianism and intolerance. In the tradition of Tocqueville, Deneen reconstructs how the individualism of liberal moderns leads to the strong, all-powerful welfare state.”[7] An astonishing verdict from a liberal pen!

Deneen’s claims please all those who despise the free market, globalization, and those who measure technological progress solely by its often less pleasant side-effects.

However, Deneen’s historical analysis and the narrative he builds on it do not stand up to critical examination. In his view, liberalism has finally failed because it was successful. Failure through success and through the fulfillment of logical consequences is the form of argument Marx uses to describe the development of capitalism, and how he predicts its end: its success will lead to its collapse and the emergence of something new, to the expropriation of the expropriators, to the death of the state, and finally to a communist society.

It is difficult to say how far Deneen was more or less unconsciously inspired by this Marxist form of argumentation—Marx is one of the authors Deneen quotes with approval on the subject of “alienation.” It is not surprising, however, that Deneen’s claims were received with more sympathy in the US by left-wing progressive liberals than by conservatives, since such claims please all those who despise the free market, globalization, and those who measure technological progress not by the gains in prosperity it has brought us, but solely by its often less pleasant side-effects.

Does Liberalism Have a Destructive Anthropology?

Deneen settles accounts with all varieties of liberalism, both the classical form, considered today in the US as conservative and market-oriented, and also notoriously labeled as ‘neoliberal’, and the left-progressive and state-interventionist variant. According to Deneen, both are fruits of the same tree and the same corrupting spirit. To this day they play into each other’s hands. What is reprehensible about liberalism, however, is not its own objectives such as freedom and the preservation of human dignity, but its view of man—for which reason we are left wondering how liberalism was able to develop an ideal of freedom and human dignity worth preserving when its anthropology is so fundamentally wrong. But this is only one of the many inconsistencies in Deneen’s book. First, let us look closer at his claims.

According to the classical pre-liberal and Christian understanding, which, according to Deneen, liberalism has always systematically fought against, man is not free by nature, but rather freedom must be learned. This is only possible under guidance, by authority, by self-control and the practice of the virtues. Liberalism, he says, has understood freedom as mere autonomy of the individual and thus as the ability to do what one wants. Liberal voluntarism destroyed the humanistic educational ideal, indeed the Liberal arts and liberal education in general, which was based on the practice of self-control and virtue, and this caused the loneliness and “alienation” of the individual. It has also made, he adds, the individual dependent on the all-competent bureaucratic welfare state. The liberal combination of individualism and statism, of market and state, supposedly leads to the dissolution of all communal ties, above all those of the family, but also of other communities, from which man as a relational being draws his moral resources. Thus, according to Deneen’s analysis outlined here, the modern person has become both individualistic and a believer in the state.

Deneen excludes in his narrative the enormous influence of socialist ideas in history. Nor is there mention of the extremely successful neo-Marxist Cultural Revolution of the 1960s.

The market economy and globalization, Deneen adds, contribute their part to handing people over to the forces of this individualistic egocentricity: they promote the pursuit of self-interest, the maximization of consumption and, if possible, the aspiration to ascend to an elite that is more and more distinguished from the masses of people. The consequences are increasing social inequality, to go along with the plundering and destruction of nature. Thus, the whole anti-“neo-liberal,” eco-socialist, civilization-critical, and technology-critical argumentation is tried, whereby everything is blamed on “liberalism,” which appears in Deneen’s narrative as the only significant actor in the history of the last two hundred years. Deneen excludes in his narrative, to the greater shame of liberalism, the enormous influence of socialist ideas in this history, socialist ideas with which liberals often made pacts or were forced to compromise. Nor is there mention of the extremely successful neo-Marxist Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, which, as liberal intellectuals often lament, is still effective under various guises today. For Deneen, there simply has not been anything else but liberalism’s destructive force in the last two centuries.

An Idealized Past and the Maligned Masterminds of the Modern Age

The antithesis of this narrative of decadence is provided by Deneen’s classical humanist tradition and its heroes: Plato, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Edmund Burke, Tocqueville. The villains, on the other hand, are Machiavelli, Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes and especially John Locke, along with, not surprisingly, J.S. Mill, and finally, and on this we might rather agree, John Dewey, who is less well known in Europe, and astonishingly enough Deneen also includes in this list F. A. Hayek. Likewise—and this makes one sit up and take notice—the Founding Fathers of the United States, especially James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, co-authors of the Federalist Papers, have to dodge an attack. According to Deneen, their aim was to alienate people from local communities and to create a bureaucratic central power, and to create an elite that was detached from the popular masses and their interests, serving instead the economic and commercial interests of the nation.

Deneen, moreover, reinterprets the principle of representation rooted in European history, and thus also the Anglo-Saxon tradition of parliamentarism, as an anti-democratic vehicle for the disempowerment of the people, and in contrast praises direct decision-making in smaller, local and morally and religiously homogeneous communities. The author, however, understands these not only as a historical model, but also as an acute instrument to defy the liberal “anti-culture,” as he calls it, through new forms of political practice.

Deneen deliberately does not offer a practical alternative of a political, economic or institutional nature, or a new political theory, but only a strategy of practical resistance in local communities.

However, Deneen is by no means advocating a return to the past. He wants to save what he believes to be the “admirable ideals” of liberalism for the future: human dignity and true freedom. Surprisingly, he moreover speaks of the “achievements of liberalism” which must be acknowledged and built upon, “abandoning the foundational reasons for its failures.”[8] – He deliberately does not offer, however, a practical alternative of a political, economic or institutional nature, or a new political theory, but only a strategy of practical resistance in local communities. Praised are the Amish, the ecological cultivation techniques in the spirit of the award-winning (also honored by Obama) agrarian humanist Wendell Berry, and the “Benedict Option”—the withdrawal from the majority society in old-native communities—and all this in the hope that this will spontaneously lead to something new and ultimately a better world.

The Misunderstood Political Project of Modernity

But what Deneen calls a moral alternative to an inhumane world of market-based globalization, ecological exploitation, growing inequality, bureaucratic overreach of human life, and the uncontrolled power of elites, is actually a dead end of illusions. Why? Because it disregards the real preconditions of the modern world’s emergence, the institutional prerequisites for securing freedom, and the economic laws and necessities required for humanity’s survival in prosperity and dignity. It chastises the modern project, which began not with Machiavelli—as Deneen claims—but with Jean Bodin. It was a project of not basing political institutions on individual virtue and high philosophical-ethical claims, but to be content with the moral minimum necessary for the peaceful coexistence of people of different faiths and with different ideas about what is good. Modern political thought therefore begins with the insight, most radically formulated by Thomas Hobbes, that the conflict-laden establishment of the Summum Bonum as a political goal must be replaced by the avoidance of the Summum Malum, civil war.

The signature of liberal constitutionalism was the insight that freedom was not to be secured by the virtues and actions of individual rulers, but by the rule of law.

Even if Bodin and Hobbes were not liberals in the sense of promoting modern constitutionalism, which was essentially directed against absolutism, the signature of modernity and finally of liberal constitutionalism was the insight that freedom was not to be secured by the actions of individual rulers, but by the rule of law—precisely independent of the virtues of the individual rulers. This was a decisive advance over the idea of limited rule, which had its origins in the Middle Ages, but was still based on the Aristotelian idea that the ideal commonwealth had the virtuous ruler as a prerequisite, and that the laws were to lead men to virtue.

But the liberal conception of the rule of law, which is not founded on virtue, does not entail—here lies the great misunderstanding—that a new concept of freedom has been introduced in the form of individualistic arbitrariness. What is new is merely the differentiation of the level of the political (the task of the state) from that of morality, or from the standards for a good individual life.

The fact that the state was understood as a means of securing freedom meant that it would no longer have the task of acting as an arbitrator or even as an educator in questions of morality and religion.

The fact that the state was no longer understood as a highly moral institution, but pragmatically and instrumentally as a means of securing freedom, and that instead of the virtues of rulers, the rule of law was to become foundational—hence the importance of the separation of powers—did not automatically mean lowering the goals of morality or establishing a new concept of freedom. Rather, it meant that political authority would no longer have the task of acting as an arbitrator or even as an educator in questions of morality and religion. In this, liberal constitutionalism, without its proponents being aware of this, is in the tradition of Thomas Aquinas, in whose writings one can find that the state’s laws have the task of punishing, above all, those actions “which are to the detriment of others and without whose prohibition human society cannot be maintained, such as murder, theft and the like”[9]: everything else is a matter for God, not the task of men—a very restrictive and in this sense liberal political criterion.

Methodological Weakness: Inappropriate Comparisons and the Confusion of Texts with Realities

It would be destructive to Deneen’s rhetorically brilliant narrative, which on closer inspection proves to be rather simplistic from an analytical perspective, to consider such historical implications along with real political problems of the exercise of power and of securing freedom, or to consider institutional and—as will be discussed later—economic and political special-interest concerns. Deneen’s “reality” is found in books and classical writings. In the texts of Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas, he sifts through the ideal past; in those of Machiavelli, Bacon, Hobbes, Locke, J.S. Mill, and Dewey, which he lumps together, he identifies the demon “liberalism” that destroyed the former world.

Deneen fallaciously compares the ideals and normative recommendations drawn in the books of classics with the social, political, economic and technological reality of today's world.

Deneen uses the questionable method of all so-called neo-Aristotelians: he fallaciously compares the ideals and normative recommendations drawn in the books of classics—i.e. a “reality” consisting of texts—with the social, political, economic and technological reality of today’s world. This is a category error, analogous to the bad habit of leftist utopians who sketch an ideal image of socialism as a possible reality, but then recognize the reality of realized (and failed) forms of socialism not as a failure of this ideal, but as a betrayal of it, while still upholding the ideal of “real” socialism as a still possible reality and as sketched out in their own classic texts. Deneen makes the same mistake in the opposite way: The past is judged on the basis of ideals found in philosophical texts of the past, the present on the basis of today’s social, political and economic reality, and both are then compared.

Thereby the “classics” are mostly mentioned selectively and warped for the purpose of the narrative; the real world understandably comes off looking badly when compared with this idealized model. Because of this misconception, the real—social, political and economic—conditions of those “classical” times, as well as their actual level of morality, are not discussed. For example, there is no discussion of the real Athens or Sparta in Aristotle’s time or the life of the broad masses in those pre-industrial times that were overcome by liberalism and industrial capitalism. To compare the world that capitalism, market economies, and liberal democracy created with the theoretical concepts of past philosophers is methodologically inadmissible and nonsensical, just as it is nonsensical to try to understand the world today simply from the texts of the classics of modernity. Of course, one must compare theories with the reality that results from their application—and many classical ideas do indeed have an excellent track record. What one cannot do, however, is to measure today’s reality against the normative ideals found in classical texts of the past and to derive a value judgement about today’s reality from this. In order to arrive at such a value judgement, today’s reality must be compared not with texts from the past, but with the real conditions of that past. Based on such a comparison of social, economic and even moral realities, our present “liberal” world would probably come off looking better than any other epoch! This is essentially due to those liberal forces that Deneen misunderstands and demonizes: the institutions of the liberal constitutional and legal state, the representative, parliamentary democracy embedded in them, the free market, capitalist entrepreneurship, scientific and technical progress and innovation, international trade and globalization.

The Market, Spontaneous Order, and Morals

As an authority securing freedom, the liberal state—within the limits necessary for the preservation of civil coexistence in peace and justice—is not only the guarantor of the freedom of different life plans that concern the “good life,” but also the protector of the free market and the “spontaneous order” of society created by it. At first Deneen seems to agree with this, but then he denounces the market as a mere product of the modern state—and on this he is historically and factually wrong. What is overlooked here is that the market economies that exist today are not organized by the state, but rather, for the most part, handicapped, over-regulated, and often misregulated by the state, without a genuinely liberal principle of order. It is precisely to the extent that they also lose their actual “market economy” quality, namely to create those incentives that almost inevitably combine legitimate self-interest—not selfishness—with the promotion of the best drives in people, thus creating that mass prosperity that has never been seen before in the history of humankind. Adam Smith called this the “invisible hand,” because it is a hand that does not exist. The non-existent hand is the market, which works through the anonymous price system, probably the most powerful, efficient and morally best instrument of cooperation and coordination that humankind has ever known.

Market-economy cooperation among free individuals is not morally corrosive; it only becomes so through misguided political incentives.

Markets and entrepreneurial competition not only create prosperity, but also encourage both a willingness to take risks and a sense of responsibility. They also encourage specifically entrepreneurial and commercial virtues such as honesty and reliability, and they promote trust as the most important and scarcest entrepreneurial resource. Market-economy cooperation among free individuals is not morally corrosive, as the communitarian theory claims; it only becomes so through misguided political incentives and the hunt for benefits, privileges, subsidies and state guarantees that are promoted by market interference, giving influential persons—usually the powerful and financially strong—competitive advantages at the expense of others. Thus, in cooperation with large companies, regulations are promoted that promise an economic advantage over competitors—“crony capitalism” is the key concept here. It is not surprising that there is no paradise even in a society based on a market economy and capitalist entrepreneurship, and those in such societies are certainly familiar with abuse, fraud and incompetence. However, these deficiencies are not intrinsic to the market system, but rather atypical to it—in contrast to all statist solutions, especially socialism, in which, instead of competition, there are systemic and system-preserving privileges, favoritism and the elimination of competitors, not through better products, but through privileged relationships, the exercise of power, and the deprivation of freedom.

The “War against Nature” through Its Mastery: Technological Criticism

Even though Deneen acknowledges that liberalism has brought incomparable freedom and unprecedented prosperity to humanity, he says that it did so by waging a devastating “war against nature” at an intolerable cost and loss. The modern project of dominating nature is for him the original sin of liberalism and the reason for the project’s self-destruction. However, Deneen’s plea for a return to a “natural” way of life ignores the fact that nature is not at all well-disposed towards humanity but is, in fact, its enemy. According to the Christian view, nature was not so from the beginning, but rather, as a consequence of humanity’s Fall, it only became so through the expulsion from paradise.

Deneen’s disdain for technological progress, which is deeply contrary to Christian tradition proves to be a form of aesthetic-professorial cynicism.

Without the blessings of modern technology and medicine, people would still be exposed to the forces of nature of all kinds: famine, poverty, misery, subsistence farming, and lack of education would be the norm. There remain plenty, but fewer and fewer, regions on earth, and people in them, where we can still see what this means. In view of today’s enormous challenges, but also the successes in the fight against poverty, Deneen’s disdain for technological progress, which is deeply contrary to Christian tradition—it is part of the mission of creation to “subdue the earth!”—proves to be a form of aesthetic-professorial cynicism. The COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, shows what untamed nature entails: a global threat by a deadly virus. And it shows that it is the materially most highly developed societies that are most likely to get such problems under control; the members of poor nations are largely helpless and suffer most. This also applies to global warming: The best strategy to help the poor, says Danish Economist Bjorn Lomborg, is to enable them to rise to our prosperity, to bring them legal security and capitalism. For in prosperity, climate change cannot be better prevented, but, if it cannot be slowed down, we can live with it in a humane way, because we possess the technologies, energy resources, and institutions to adapt to what cannot be prevented.[10]

Intellectual Populism and a Questionable Handling of Sources

Deneen refuses such thoughts because he uses the entire leftist anti-capitalist, anti-market and anti-globalization arsenal of arguments in an almost “populist” manner. Yet the intricate, often seemingly contradictory web of his arguments, quotations and references, does not stand up to closer scrutiny. In detail, it abounds with tendentious textual interpretations and out-of-context and thus distorted quotations. On closer inspection, Deneen’s handling of the sources proves to be charlatanism.

To give an example, John Locke advocated the typically liberal view that “natural freedom” meant the freedom to do what one wants and what one feels like doing. What Deneen conceals is Locke’s addition: “within the limits of natural law.”[11] The fact that Locke was a natural law theorist in the tradition of the Anglican theologian Richard Hooker, whose thought in turn was in line with Thomas Aquinas, does not fit into his narrative.[12] The historical relationships are more complicated and complex.

Deneen is not interested in understanding economics; it does not belong to the reality that is relevant to him.

The use of a key passage from F. A. Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty also appears to be charlatanism.[13] Hayek’s astute economic insight—referencing the French sociologist Gabriel Tarde in this context—that in a progressive society, unlike in a static society, material progress ”takes place in echelon fashion.” That is, material progress happens in such a way that the rich make it possible through their luxury consumption that it will later become mass consumption for the next generation. Deneen reinterprets this as a justification, even idealization of ever-growing inequality—whereas in reality it is the exact opposite, namely an economic argument for the progressive levelling of inequality in terms of prosperity and quality of life. Deneen is not interested in understanding economics; it does not belong to the reality that is relevant to him.

His dealings with the Founding Fathers James Madison and Alexander Hamilton have already been mentioned. This is a deliberately out-of-context interpretation, whereby the actual concern of the constitutional fathers criticized by Deneen is concealed and falsified, namely the overcoming of partisanship, small-scale special interest politics, and demagogy. The goal of the Founding Fathers was to deal with the consequences of the inescapable weaknesses of human nature, to prevent local concentrations of power and the “mischief of factions” that are a consequence of direct democracy in small communities, and that endanger the freedom of the individual: and they attempt to mitigate these problems through the overarching protection of a constitutional state and republican government. (Even a direct democracy like the Swiss one is only a supplement to the representative democracy that Deneen seeks to ridicule: it does not replace it; moreover, it is integrated into an overarching rule of law whose norms do not depend on small group decisions at the local level).

His dealings with the Founding Fathers James Madison and Alexander Hamilton are a deliberately out-of-context interpretation. Their actual concern is concealed and falsified.

To conceal Madison’s true intentions (in Federalist 10), Deneen suppresses in an important quote[14] a part of the sentence in which “[through] patriotism and love of justice [elected representatives] will be least likely to sacrifice [the true interest of their country] to temporary or partial considerations,” which is mentioned in favor of a national government.[15] On the other hand, and this is also not mentioned, precisely those areas that are classically considered sovereign powers and of direct importance to citizens should (according to Hamilton) be transferred to, or left with, local communities as far as possible: “the ordinary administration of criminal and civil justice […] and [service as the] visible guardian of life and property.”[16] The realistic anthropology on which the recommendations of the Federalist Papers are based, however, is suppressed by Deneen’s tendentious citation.

Deneen cannot accept that the authors of the Federalist Papers, like Kant, pit the republican against the (direct) democratic principle. His communitarianism calls for a freedom that consists in democratic participation in local communities. He considers republican, large-scale, “supra-regional” government based on the principle of (parliamentary) representation to be one of the liberal demands that contribute significantly to destroying local communities and ties, as well as community spirit. Moreover, he believes it tends to replace an orientation toward the common good with a situation in which the individual aims at mere self-interest, while at the same time making the latter dependent on a superior and all-dominant state and its bureaucracies.

Of course, it is fair to ask whether history would not have been better if the North American states that now make up the United States had remained sovereign states, more like Europe, without an overarching central government (even if sensible decentralization always remains an asset). But even Europe, consisting of many sovereign nation-states, has not been spared the phenomena that Deneen laments: not even the small, federalist Switzerland with its direct democracy.

“Liberty of the Ancients” vs. “Liberty of the Moderns”

Deneen’s concept of freedom corresponds in political terms to what Benjamin Constant, the great liberal theorist of the early nineteenth century, called the “liberty of the ancients,” freedom that consists in political participation and thus at the same time in, and dependence on, the community, its norms, values, etc. The “liberty of the ancients” differs from the “liberty of the moderns” which is characterized precisely by being left in peace by the community, in particular by the state, and in being guaranteed the right to live according to one’s own ideas, to pursue business independently of governmental dictates.[17]

Constant’s distinction is still relevant today; Deneen does not mention it because its mention would destroy his narrative. The distinction shows that the alternative is not one of “bureaucratic central government,” on the one hand, and “local, participatory communities” on the other, but, in Constant’s words, the alternative between “ancient liberty” which “demands that the citizens should be entirely subjected in order for the nation to be sovereign, and that the individual should be enslaved for the people to be free.”; and “personal freedom,” which is precisely freedom from politics, but also from the police, or an independence protected and secured by the state to do what you decide and to live as you please: “The aim of the moderns is the enjoyment of security in private pleasures; and they call liberty the guarantees accorded by institutions to these pleasures.” Among the ancients, on the other hand, “the individual, almost always sovereign in public affairs, was a slave in all his private relations.”

Certainly, one can also distort this modern understanding of liberty as personal independence or autonomy. The question is whether this itself is a work of “liberalism.”

The great error consists in thinking that this “modern liberty” is hostile to the community. It is not so, because it frees human freedom and inventiveness to organize itself, to associate, and of course grants protection especially to the family, which enables it to carry out its tasks independently. Compare this to the arbitrary anti-liberty regime of French absolutism, but also compare it to the tyrannical communitarianism of the ancient family![18]

Certainly, and here Deneen is right, one can also distort this modern understanding of liberty as personal independence or autonomy. The question is only whether this itself is a work of “liberalism.” One can only come up with this idea if, especially in the case of a classical liberal like Benjamin Constant, one also rips this claim out of its broader context. For in Constant’s work we also read: “Every time governments pretend to do our own business, they do it more incompetently and expensively than we would.”[19] It seems difficult to recognize a causal nexus between such a program and a welfare state that interferes in all areas of life, and it is implausible to make people who thought like Constant jointly responsible for such a development.

Admittedly, this too is only a text, not in every respect beyond all doubt, and it has time-dependent weaknesses and one-sidedness. The development of the modern world has not followed the logic of texts, but actual political decisions, sociological as well as economic developments, the logic of institutional action and the often irrational, incompetent or irresponsible reaction of politicians to crises or catastrophes. It is precisely on this level that Deneen’s narrative becomes entirely questionable for obvious reasons that cannot be discussed in detail here.

“Real Existing Liberalism” in a State of Imbalance

By attempting to cover up the deep differences, even contradictions, within the liberal world of ideas, and to speak quite simply of liberalism as if it were a single historical force, Deneen not only makes it too easy for himself, but also distances himself from historical reality. But independently of this, as mentioned at the beginning, critics also claim that he has recognized and addressed sore points of “liberal” modernity. And these are points that should actually be a concern for every classical liberal, all the more so if his or her liberal attitude is rooted in the Christian faith.

The discomfort in the globalized world of growing inequality, and the loss of meaning and community, as addressed by Barack Obama’s praise of Deneen’s book, are first and foremost consequences of a huge political and media influence, along with an education system that, at least in Europe, clearly promotes a lack of understanding of economic interrelationships and aversion to everything related to free market economies and capitalism. Catholic social teaching has also played its part here, not always in the same way, but nevertheless in its general tendency and through many of its prominent representatives in both teaching and journalism.[20]

More economic and economic-historical education would be a good antidote to the socialist infiltration of the liberal and humanistic ideal of education.

The unease is therefore often based on false information and ignorance, which is promoted by precisely that kind of non-economic or even anti-economic, humanistic, i.e. “liberal”, education whose disappearance and disregard Deneen laments. It is precisely “humanistic” intellectuals like him who are partly to blame for the fact that young people remain in economic and economic-historical ignorance and accordingly develop false images of the enemy. More economic and economic-historical education would be a good antidote to the socialist infiltration of the liberal and humanistic ideal of education.

The Failure of the Liberals and the Diversity of “Liberalisms”

If one looks more closely, most of the undesirable developments—especially those of an economic and social nature—are not to be attributed to “liberalism” as such, but rather to a lack of liberalism, to a betrayal of it, often precisely by liberals, and to liberal inconsistency and weak character in the face of illiberal tendencies, to which they cave for “social” or “ecological” reasons.

It is not “liberalism” that has supposedly failed, it is interpretations of it and certain forms of it that owe their existence to the betrayal of the many liberals who became social democrats.

In reality, it is not “liberalism” that has supposedly failed, it is interpretations of it and certain forms of it that owe their existence to the betrayal of the many liberals who became social democrats. They assimilated the view that the market must be tamed so that it does not serve only the rich, as is often wrongly asserted, and that its results must be corrected by redistribution for social reasons; in addition, the individual should be protected as completely as possible against uncertainties by a state safety net—not only for actual extreme emergencies, but also where one could help oneself (read Ludwig Erhard to see what a deep perversion of his liberal concept of the “social market economy” this is). At the same time, this deprives of oxygen the family, as a natural community of reproduction, upbringing, and provision. Here too, Deneen has a point, even if his analysis of the historical genesis of this development is wrong. The modern welfare state is not a product of liberalism; its history, which begins with Bismarck, is far more complex.

But the liberalism of the 19th century is also partly to blame for the steadily increasing power of the state. No less than F. A. Hayek lamented the destruction in the wake of liberal statism of the “corps intermédiaires,” the social voluntary communities and corporations—many of them also of a church or denominational nature—acting between the individual and the state. This grossly disregarded the principle of subsidiarity that is also held in high regard by liberals today.[21] Likewise, betrayal comes from a liberalism that offers a hand in furthering the originally socialistic program of Friedrich Engels to integrate men and women as completely as possible into working life and the labor market, aiming thereby at destroying the bourgeois family and thereby, having as a side-effect the socialization of education. This, as well as a number of demands of the neo-Marxist Cultural Revolution—such as the idealization of a complete decoupling of sexuality and procreation, or their “anti-authoritarian” educational models—represent “liberals” today, and not only in the United States. This is indeed a problem. Yet all this cannot be derived from the nature of liberalism, at most it can only be derived from certain historically contingent interpretations of it.

The Liberal Distinction between the Political-Legal Level and that of the Morality of Individual Lifestyles

Liberalism was never an ideologically homogeneous entity. Thus J.S. Mill, for some, is the liberal par excellence, but for others the first socialist—and a case can indeed be made for that. He was of the opinion that although production should be left to the market, the fair distribution of the national product was a matter for the state. On the other hand, his concept of autonomy and freedom is considered typically liberal, although as a liberal thinker one can take a different view on this. Mill’s disregard for customs and tradition was certainly an understandable anti-Victorian reflex against the repressive power of public opinion, but as such not the final conclusion of liberal wisdom, as demonstrated by the liberalism of F. A. Hayek and his understanding of freedom, which is more in line with Burke and Tocqueville. It is no coincidence that Hayek dedicated his book The Road to Serfdom to the “socialists in all parties”!

J.S. Mill's concept of freedom is not suitable for the non-political sphere, neither for the family nor for education and formation. A pedagogy based on it creates disorientation and has a destructive effect.

Mill’s concept of freedom is particularly problematic. For him, the ultimate justification of individual freedom consists in the mere exercise of freedom—whatever the purpose and whatever good is pursued with it, the main thing is to realize one’s own individuality and not to harm others.[22] This is a useful criterion at the legal-political level—Mill’s contemporary, the Catholic liberal Lord Acton also said that in political terms liberty is the highest end and not just a means to something higher.[23] Otherwise the state would have the task of “educating” our freedom. Precisely for this reason, however, it becomes clear what Mill’s concept of freedom—and in his wake that of many liberals—is ill-suited to do: it is not suitable for the non-political sphere, neither for the family nor for education and formation. A pedagogy based on it creates disorientation and has a destructive effect. Here Deneen is right, but only insofar as the mistake lies in “totalizing” a political, morally “neutral” concept of freedom, and in seeing the essence and fulfillment of freedom in the freedom of choice alone, and in accepting this even for individual morality and as fundamental for education. This reverses the modern distinction between the political sphere and the morality of a good life.

John Locke understood freedom to mean the freedom to do what one wants, but “within the limits of natural law.”

As I said, John Locke, who is cited by Deneen as the chief liberal representative, had a different concept of natural freedom: he understood it to mean the freedom to do what one wants, but—and this is left out by Deneen—“within the limits of natural law.” Locke therefore distinguishes between natural and political freedom, the latter which follows a specifically political ethics for the purpose of securing individual freedom and its foundations in physical integrity and property.

It is not the political concept of freedom of classical liberalism that is problematic, as Deneen insinuates, but the abolition of the modern distinction between the political-legal level and that of the morality of individual lifestyles, an abolition that he also advocates. The decisive political-legal—especially constitutional—factor is that people are given the freedom to make their own choices and lead their own lives, as long as these do not conflict with the same freedom of others. This is not so in the case of education and formation, or of morality. For these it is not exclusively important—even if it is fundamental—to educate people in independence and the ability to make their own choices; it is also crucial to learn to practice the ability to distinguish good from evil and—to the best of one’s knowledge and conscience—also to put into practice what has been understood as good and righteous. An education to freedom is thus education in freedom, but a “value-bound” education, that is, one that is not morally neutral, but spurs one on to choose and do what is good, and one that is able to offer standards for such choices. Precisely this is the nature of educational authority, but it can have an educational effect only if it is able to stimulate freedom, insight, and self-responsibility in the one being educated.[24] Nobody can know with certainty if the values that are mediated by one’s education are the “absolutely” correct ones. In the end, in the course of his life, even in conflict, often in resistance to or even in—often fruitful—rebellion against one’s own education, each one must form one’s own conscience independently and with one’s own responsibility. And this can be done only if one has enjoyed an education and formation that is value-based in this sense and not “value-neutral.”

The “value-conscious” liberal must clearly distinguish the level of personal conduct, wherever the freedom of choice between good and evil, morality and virtue, is at stake, from the political level.

The “value-conscious” liberal must walk a tightrope. He must clearly distinguish the level of personal conduct, wherever the freedom of choice between good and evil, morality and virtue, is at stake, from the political level. The latter is that level of the legal defense of the freedom of everyone, which makes possible the peaceful coexistence of citizens who have divergent views on good and evil, morality and virtue. Deneen would fall on this tightrope walk, if he wanted to take it at all, because he denies himself this distinction and thus also misreads history. But the same is true of many “progressive” liberals or “left-wing liberals” who, strangely enough, rely on statist, state-interventionist policies to realize their agendas, which one would rather expect from socialists. They want to impose their own, ultimately egalitarian moral concepts—and more recently also identity-political demands—with the power of the state, and thus unintentionally participate in the game of the anti-bourgeois cultural revolution.

The Moral and Social Foundation of a Free Society

Many demands of today’s “liberal-progressives” or “left-wing liberals” are an understandable reaction to unjust and often brutal discrimination in the past—and in many places also in the present—of women, and of ethnic, racial, religious, and sexual minorities. This becomes a problem, however, as soon as the injustice of discrimination is addressed with socialist-statist solutions. Liberals, too, are increasingly speaking out today in favor of socialist, state-imposed solutions—on socio-political issues about which they often agree with social democrats and socialists. One thinks of topics such as the inheritance tax, “women’s quotas”—or the controversial same-sex marriage. There has been the implicit redefinition of traditional marriage—the basically, though not necessarily factually, reproductive union between man and woman, which in turn is based on their biological-reproductive and psychological complementarity—to what is in fact a “socialist” (and “constructivist”) proposal. When, instead of the liberal legal equality for those who differ—“equality before the law”—which, in recognition of equal human dignity, otherwise treats inequalities before the law equally, the socialist solution decrees the legal levelling by the state of such inequality—inequality that is due to natural diversity. But such disparities and differences are socially and morally relevant, for they form the social foundation of a free society and function—as does private property—as a bulwark against presumptuousness of state power and politics.

Today, the liberal project must be defended both from conservative reactionary critics and from its left-wing gravediggers. The latter do indeed undermine the social and moral preconditinos of a free society.

This is where the liberals have failed, in that they missed a liberal solution to counteract discrimination against sexual minorities. This solution would have consisted in respecting the diversity of sexual minorities and enabling appropriate legal regulations for overcoming their discrimination, while leaving the identity of the family, which is based on traditional marriage, untouched as a reproductive and provident community. Let us not forget: the sexual orientation of a person and his or her corresponding actions must be indifferent to the state and its law: they are a private matter. But this is not the case with marriage as a community of reproduction and provision for offspring. Marriage is of eminent social, economic and political importance, and therefore of public significance. For this reason, the creation of “same-sex marriage” is, from a liberal point of view, an absurdity, because it gives public recognition to a relationship that is relevant purely on the private level, which means an unjustified privilege in comparison to marriage as a community of reproduction and provision.[25]

Today, the liberal project must be defended both from conservative reactionary critics and from its left-wing gravediggers. The latter do indeed undermine the social and moral preconditions of a free society and thus open the door to the state’s—“constructivist”—control over the individual and over natural communities like the family. Liberals need strong ethical convictions and a liberal society needs a social foundation capable of shaping such convictions. It was the “leftist” cultural revolution that championed the opposite against liberal, bourgeois society, and it did so not without consequences and in an extraordinarily effective way.

Many of the problems we have with freedom are side effects of progress that is good in itself. The increasing liberation of people from the constraints of natural circumstances, which once also determined gender roles and social structures, is also leading to an increase in normative disorientation. It has led to a freedom—not least of all sexual freedom, but also a rise in demands generated by prosperity—that we have not yet really learned to use without undermining the moral and social foundations of a free society.

Relativists and agnostics are neither better liberals nor better democrats—indeed, they may one day turn out to be the gravediggers of freedom and democracy.

The religious and moral neutrality of the state does not mean religious and moral neutrality of the citizen, of education, of social life. Whoever claims this only plays into the hands of the enemies of freedom, because in doing so he legitimizes the steady increase in the state’s power of disposal over the individual, his property and his freedom—or at least weakens the resistance against it.

Relativists and agnostics are neither better liberals nor better democrats—indeed, they may one day turn out to be the gravediggers of freedom and democracy. What the liberal—even, as in the case of the writer, a Catholic or otherwise “value-bound” liberal—needs to be concerned about is the defense of a political culture that keeps the state out of such issues, and prevents it from imposing any agnostic, relativistic moral concepts or ideas of a “socially just” society from above—even if this were supported by democratic majority decisions. For respect for minorities is part of the essence of the liberal constitutional state, which is committed to a liberal democracy based on the rule of law.

Political Freedom or Social Equality?

The state has no traditional or modern morality to impose on society. To take the much-cited Böckenförde dilemma[26] further: free society, the secular, liberal constitutional state, lives from resources that it cannot generate itself nor undermine with impunity. The fact that these resources are being depleted is not a consequence of liberalism, but of a general cultural crisis. The churches are partly to blame, as they have failed completely in this respect; the schools, education and pedagogy are partly to blame—think of the destructive effects of the ideas of “anti-authoritarian” education in the 1970s. But those liberals who gave these ideas room, and even assimilated them, are also partly to blame, because they did not recognize that they were ideas deeply opposed to the liberal cause.

By describing classical and left-progressive liberalism as variants of the same basic idea, and by ultimately understanding them as two forms of liberalism appearing one after the other in history and as still competing forms of that same idea today, Deneen blurs the decisive difference between a liberalism rooted in classical thinking and constructivist-statist, left-liberal progressivism. More closely, it blurs the crucial difference between a political theory of political freedom based on the rule of law and a political theory of social equality based on the rule of political arbitrariness. These are, to put it very simply, the two great opposites. The opposition was originally that between liberalism and socialism. By assimilating socialist elements, progressist left-wing liberalism is in conflict with classical liberalism. Deneen blurs this contradiction by constructing the great antagonism as being one between liberalism and “communitarianism,” the latter which, it is not surprising, clearly incorporates socialist motives, especially in its aversion to any form of social inequality, including performance-based inequality, hence its contempt for the market economy and capitalism. F.A. Hayek’s verdict that political conservatism is always dragged along by socialist ideas because of its disregard for political principles is also proven true here.[27]

Liberals should have the courage to state clearly that there can be no free society without a social substructure that is itself not modelled on the requirements of political freedom.

Liberals should have the courage to state clearly that there can be no free society without a social substructure that is itself not modelled on the requirements of political freedom—just as democracy requires social structures that are not themselves democratic. This is exactly what the liberal Zurich state law professor Dietrich Schindler taught decades ago in his classic treatise Verfassungsrecht und soziale Struktur (“Constitutional Law and Social Structure”) A liberal state that emphasizes the independence and freedom of the individual as well as democracy—which is “ultimately a negation of subordination and commitment”—requires “compensation through opposing principles,” “moral prerequisites,” “self-discipline, moderation, the will to communicate…,” yes, according to Schindler, as the American constitutional Fathers believed, it requires “a code of virtues that citizens had to comply with.”[28]

Both freedom and active participation must be practiced, they must be learned. This is done through processes of education that respect the person as a free being, but do not themselves obey the political logic of freedom and democratic participation. Fine differentiation of levels is not Deneen’s thing. However, liberals are also guilty of confusing the levels when they advocate socio-political concepts that go beyond the granting of legal equality in political and civil life to instead aim for an egalitarian, legally “constructed” transformation of society in its interior. Even if law and order have the task of reacting to social developments, this does not mean that new forms of social life—such as new forms of “family”—should be invented. In any case, one cannot derive such demands from the essence of liberalism. It was the “left” Cultural Revolution that championed this against liberal bourgeois society, and it continues to do so in an extraordinarily effective manner, because many liberals today have become their allies out of pure short-sightedness.

Notes:

[1] Patrick Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018).

[2] Jennifer Szalei, “If Liberalism Is Dead, What Comes Next?” New York Times (January 17, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/17/books/review-why-liberalism-failed-patrick-deneen.html, accessed October 19, 2020; and Ross Douthat, “Is There Life after Liberalism?” New York Times (January 13, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/13/opinion/sunday/life-after-liberalism.html, accessed October 19, 2020.

[3] “Liberalism Is the Most Successful Idea of the Past 400 Years: But Its Best Days Might Be Behind It, According to a New Book” The Economist (January 27, 2018), https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2018/01/27/liberalism-is-the-most-successful-idea-of-the-past-400-years, accessed October 19, 2020.

[4] Tod Lindberg, “A Radical Critique of Modernity in ‘Why Liberalism Failed’: Liberalism’s Breakdown of Social Norms Has Been a Boon to Individuals but a Bust for the Shared Culture,” (January 12, 2018), https://www.wsj.com/articles/review-a-radical-critique-of-modernity-in-why-liberalism-failed-1515790039, accessed October 19, 2020.

[5] Barack Obama, Facebook Post, June 16, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/barackobama/posts/10155941960536749, accessed October 19, 2020.

[6] Renata Schmidtkunz, Interview with Patrick Deneen, “Patrick Deneen—Warum der Liberalismus gescheitert ist,” https://oe1.orf.at/artikel/662671/Patrick-Deneen-Warum-der-Liberalismus-gescheitert-ist., accessed October 19, 2020.

[7] Alexander Grau, “Das Licht, das erlosch. Eine Abrechnung. Und: Warum der Liberalismus gescheitert ist” Kultur, Kurzkritik, Rezension 1077 (June 2020), https://schweizermonat.ch/das-licht-das-erlosch-eine-abrechnung-und-warum-der-liberalismus-gescheitert-ist/, accessed October 19, 2020.

[8] Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed, 184; 182.

[9] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 96, a. 2, corp.

[10] See Bjorn Lomborg, False Alarm. How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts the Poor, and Fails to Fix the Planet (New York: Basic Books, 2020).

[11] John Locke, Second Treatise on Government, IV, 22; in, Locke, Two Treatises of Government, ed. Peter Laslett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960), 283 f.

[12] See Martin Rhonheimer, “St. Thomas Aquinas and the Idea of Limited Government,” Journal of Markets & Morality 22, 2 (Fall 2019), 439–455; esp. 443 ff.

[13] F. A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty. The Definitive Edition, ed. Ronald Hamowy in The Collected Works of F.A. Hayek, Vol. XVII (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press [1960] 2011, 96-97.

[14] Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed, 163.

[15] Federalist 10 (Madison).

[16] Ibid., n. 17 (Hamilton).

[17] Benjamin Constant, De la liberté des anciens comparée à celle des modernes (1819). Translated as The Liberty of Ancients Compared with that of Moderns, uncredited translator (Unknown, 1819). https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2251, accessed October 19, 2020.

[18] On this last point, see Larry Siedentop. Inventing the Individual. The Origins of Western Liberalism (London: Penguin, 2014), 7-18.

[19] Constant, The Liberty of Ancients.

[20] Cf. Martin Rhonheimer, “Vom Subsidiaritätsprinzip zum Sozialstaat. Kontinuitäten und Brüche in der katholischen Soziallehre,” Historisches Jahrbuch der Görres Gesellschaft 138 (2018): 6-71; and idem, “Brüche in der katholischen Soziallehre: Vom Primat der Freiheit zur staatlichen Zwangssolidarität,” in Wirz, Stephan (ed.), Kapitalismus – ein Feindbild für die Kirchen? (Zürich—Baden-Baden: Schriften Paulus Akademie, 2018), 57–78.

[21] F.A. Hayek, Law, Legislation, and Liberty: Volume II, The Mirage of Social Justice (London: Routledge, 1982), 150-2.

[22] J. S. Mill, On Liberty, in Utilitarianism, On Liberty, and Considerations on Representative Government, ed. H. B. Acton (London: J.M. Dent and Sons, Ltd.,1972), 125; 114; 136ff. Cf. Martin Rhonheimer, “The Liberal Image of Man and the Concept of Autonomy: Beyond the Debate between Liberals and Communitarians,” in The Common Good of Constitutional Democracy: Essays in Political Philosophy and on Catholic Social Doctrine (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2013), 36-71; regarding Mill see, especially, 45ff.

[23] John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton, First Baron Acton, Essays in the History of Liberty, ed. J. Rufus Fears, in Selected Writings of Lord Acton, Vol. I (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 1985), 22.

[24] See Martin Rhonheimer, The Perspective of Morality. Philosophical Foundations of Thomistic Virtue Ethics (Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2011), 213-15.

[25] A possible “right to adoption” for all does not stand in the way of this argument, for the simple reason that there is no “right to adoption”—not even for a marital community consisting of man and woman. Adoption and the ability to do so must—in each individual case—be considered exclusively from the child’s point of view.

[26] See. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Böckenförde_dilemma

[27] F.A. Hayek, “Why I Am Not a Conservative” in The Constitution of Liberty, “Postscript,” 519-33. See Martin Rhonheimer, “Warum Hayek kein Konservativer war: Ein Beitrag zur aktuellen Liberalismusdebatte,” ORDO – Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 67 (2016): 481-497. (Translator’s note: For the American audience it is worth noting that Hayek considered himself a Burkean Whig, and thus would consider Burke a part of the truly liberal tradition and not an object in his critique of “conservativism”).

[28] Dietrich Schindler, Verfassungsrecht und soziale Struktur, 5th ed. (Zürich: Schulthess Juristische Medien, 1970), 142-33.

Translated from German by Thomas and Kira Howes

For a short version of this article, that was published in the Swiss journal “Neue Zürcher Zeitung,” click here.

- Anti-capitalism

- Blog

- Capitalism and Market Economy

- Crony capitalism / Cronyism

- Democracy

- Discrimination

- Environment

- Equality before the law

- Family

- Featured Content

- Freedom and Liberalism

- Globalization

- Inequality

- Martin Rhonheimer

- Philosophy and Ethics

- Poverty

- Prosperity

- Redistribution

- Rule of law

- Social Philosophy

- Social Policy

- Social theory

- Socialism

- Society

- State, Government and Politics

- Technology, technological progress

- Welfare State