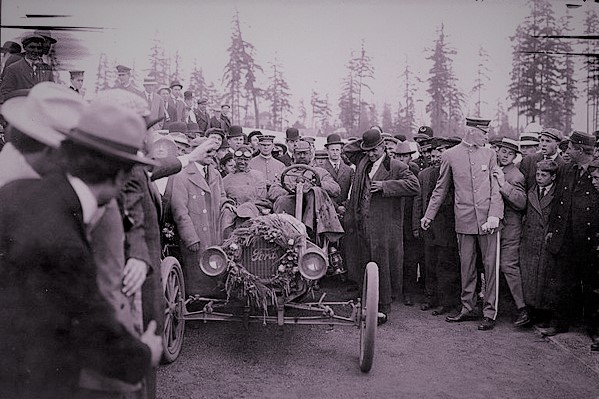

A 1909 Ford Model T, winner of the race from New York City to Seattle: Under capitalism, luxury consumption eventually becomes mass consumption. Even toilets, washing machines, and refrigerators were at first only available to the rich. Today they are standard appliances for every welfare recipient. (Picture: Wikimedia Commons)

A 1909 Ford Model T, winner of the race from New York City to Seattle: Under capitalism, luxury consumption eventually becomes mass consumption. Even toilets, washing machines, and refrigerators were at first only available to the rich. Today they are standard appliances for every welfare recipient. (Picture: Wikimedia Commons)

Human history is deeply marked by mass poverty. This was only overcome by the capitalistic industrial revolution. Now, poverty still prevails in some parts of the world, but the recipe for success has always been to increase labor productivity by securing property rights, capital accumulation, and technological innovation. This has led to a supply of increasingly better products, growth in the purchasing power for the masses, and rising living standards. Capitalism—a market economy with private ownership of the means of production—works because it serves the consumers, i.e. everyone. It is therefore the poorest who have benefited most from capitalism. Wherever political conditions allow it, this process is repeated on a global scale.

Today the social doctrine of the Church criticizes consumerism precisely as the subjective reflection of the “techno-economic paradigm,” thus attacking the foundations of today’s mass prosperity.

The official Catholic social doctrine has never really dealt with these connections. Even in its current criticism of “compulsive consumerism,” caused by the market’s alleged mechanism of “extreme consumerism” (see Encyclical Letter Laudato si’), it forgets that it is precisely this mechanism of the market that creates prosperity and that it is thus the foundation for education, culture, and a dignified life. Today, however, the social doctrine of the Church criticizes consumerism precisely as the subjective reflection of the “techno-economic paradigm,” thus attacking the foundations of today’s mass prosperity.

Another misunderstanding is that we owe the rise in the general standard of living to the pressure of the trade unions and social policy. Without these, so they say, the fruits of the market economy would only benefit the rich. This is incorrect. In certain sectors of the economy union pressures lead to wage increases, but these increases are usually at the expense of those working in less unionized industries; or else it causes price inflation and thus reduces the purchasing power of wages. General wage increases and the betterment of all—the common good—require innovation and growth in productivity and, in turn, capital accumulation. The result is, primarily, growing inequality but also a simultaneous increase in the general standard of living. This is also currently the case in economically emerging countries like China, where a part of the population is becoming wealthy, along with an ascending middle class of hundreds of millions, and only a minority that still lives in poverty.

There can be no mass prosperity without a few that rise to great riches! In capitalism, as historical experience shows, luxury consumption eventually becomes mass consumption. The first refrigerators, washing machines, and toilets were owned by the rich; they bought the appliances, which then gradually became inexpensive through mass production. Today they are the basic appliances of every welfare recipient. In contrast, an egalitarian policy of “social justice,” which counteracts inequality caused by innovation and violates property rights, can slow down the rise in the general standard of living. Or, in extreme cases, it may even generate mass poverty—as happened in Venezuela.

Pope Leo XIII spoke out strongly against any infringement of private property to improve the situation of the working class.

In the 19th century of all times, when the “social question” was still a real issue, Catholic social teaching had recognized that social justice does not consist in social equality, not even in equality of opportunity, but in the equality of rights. In his encyclical Rerum Novarum of 1891, Pope Leo XIII stated that workers have a right to protection of their life and health and that therefore appropriate protective laws are necessary—because it would be a violation of distributive justice if the state were to only protect the lives and physical integrity of the wealthy. But Pope Leo spoke out strongly against any infringement of private property to improve the situation of the working class. This would be a case of robbery and an unjust “leveling down.”

But soon, not only the Church’s social teachings, but also political Catholicism went in another direction. Towards the end of the 19th century, it was believed that the solution to the social concerns was to be found in state social policy and “social justice,” organized from the top down. Among the representatives of political Catholicism, however, there were also critics of this position. The most prominent was Georg von Hertling, professor of philosophy, member of the Reichstag, Bavarian Prime Minister and finally, from 1917-1918, the second-to-last Chancellor of the German Empire. In his 1893 paper “Naturrecht und Socialpolitik” (Natural Law and Social Policy), Hertling advocated laws to protect workers and also basic insurance, but he believed that the solution to the social question lay not in social policy but in economic and technological progress. Rather than behaving paternalistically toward citizens, the state should promote entrepreneurial initiative.

Hertling—the 100th anniversary of whose death will be on January 4th, 2019—saw in the then looming electronification of the economy the promise of a democratization of increased productivity—and he was right. Electricity, he said, and everything connected with it, would lead to a revolution in ownership structures and bring about a massive decentralization of increased productivity. Productive power, previously only possible with steam power in large industries, would soon enter every workshop through electricity. Hertling would probably also welcome the digitalization of today’s economy.

Catholic social ethicists usually think that the welfare state as it exists today is the non plus ultra of modernity. But thinking that way means burying one's head in the sand.

His economically enlightened optimism remained alien to Catholic social teaching. There were exceptions, such as Joseph Höffner and Johannes Messner, who accused the Catholic social doctrine of their time of failing (due to the influence of Marxism) to understand the value-creating function of the entrepreneur. But these thinkers were less influential than those who saw the solution in social policy, the strengthening of trade unions, and “social justice” organized by the welfare state.

Catholic social ethicists usually think that the welfare state as it exists today is the non plus ultra of modernity. But thinking that way means burying one’s head in the sand. The welfare state, with its pay-as-you-go social systems, has been overstretched and makes impossible and unsustainable promises. Financial burdens are shifted onto future contributors. Benefits are paid with increasing public debt, which is currently financed with low interest rates and may end badly. Excessive debt slows down economic growth and unjustly encumbers future generations. And indeed, the low interest rate policy, which aims to stimulate consumption by credit financing, is a cause of the denounced “senseless consumerism.” It also generates asset price inflation, making the rich richer. When the free market’s mechanism of “excessive consumption” is indicted, one should not remain silent about these governmental and monetary policy distortions. Catholic social teaching would do well to follow the motto held high by Pope Francis, “See—judge—act,” coming down from a moral high horse and facing up to the real economic circumstances. Then it could offer the Zeitgeist a real counterproposal, instead of blindly following its lead.

This article was originally published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (24 December 2018) under the title Die Wirtschaftsferne der katholischen Soziallehre. Translation from German by Thomas and Kira Howes.