Children are economically dependent and need financial support. In contrast to older people, it is not the state that provides most of these services, but the family. (Picture: Pixabay)

Children are economically dependent and need financial support. In contrast to older people, it is not the state that provides most of these services, but the family. (Picture: Pixabay)

In Austria, about half of public expenditure benefit the 60+ generation. Pensions, health care and long-term care benefits are the most important public programs aimed mainly at the elderly population. In contrast, the private social contributions made by families, which are largely received by the younger generation, are barely noticed and little documented. In his recent study, the Viennese demographic economist Bernhard Binder-Hammer shows that the social economic benefits and contributions made by families are enormous—and endangered. His findings deal specifically with Austria, but the general insights drawn from the data can be applied elsewhere.

This text has also been published by us as Austrian Institute Paper No. 31-EN/2020. You can download the PDF here.

Families provide for the needs of children and thus make the largest contribution to a society’s investment in human capital. The human life course is characterized by two long phases of economic dependence: childhood and retirement. This economic structure of the life course requires the redistribution of income between generations and over life stages. Three different mechanisms can be distinguished: Inter-generational transfers within the family, public inter-generational transfers, and wealth accumulation. [1] While in Austria the needs of the elderly are mainly covered by state pensions, healthcare, and other care services, for children the family plays by far the most important role.

Despite the central role of families, there is little data available to quantify the exact economic expenditures of families for children. While the public transfer system and its financial viability are the subject of very intensive debate, the contribution of families is hardly ever discussed, let alone measured.

National Transfer Accounts (NTAs) attempt to measure and present intergenerational transfers comprehensively, especially the support provided by families. This article provides an overview of economic support between generations based on the data of the National Transfer Accounts for Austria in 2015. Although the data discussed below pertains to Austria, the same general insights on the role of families that are drawn from it can be applied elsewhere.

Monetary Intergenerational Support (Transfers) within the Family

A central type of support between generations is the consumption of children financed by their parents. There is no data for Austria that directly records private expenditure for children directly. Transfer accounts estimate this type of intergenerational support by linking data on individual income and consumption. If the consumption of a household member is above his or her income, it is assumed that the difference is financed by support (transfers) from other household members. As it is mainly children who have no income of their own, this method mainly records transfer flows from parents to their children. Although the estimates depend heavily on the assumptions made, NTAs provide valuable information on the magnitude and direction of these economic transfers.

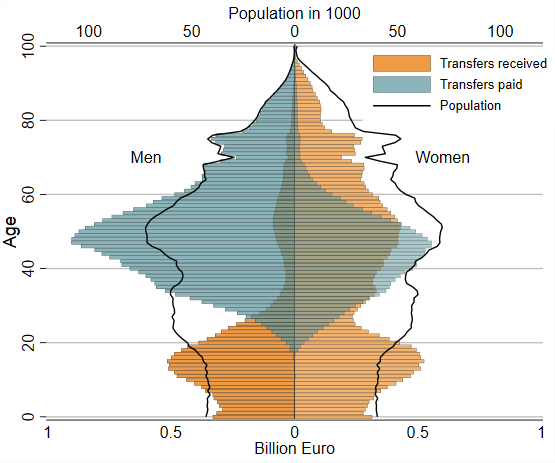

According to the estimates of the National Transfer Accounts, the total spending of families on children under 25 amounts to approximately 21 billion euros and more than 9,000 Euros per child. Figure 1 shows the total transfers received and paid by men and women in each age group. Children, adolescents, and young adults up to the age of about 25 are net recipients of intra-family financial support. On average, the highest benefits are received by children around 15 years of age, before these young adults enter the labor market and generate income themselves. The highest contributions to intra-family transfers are made between the ages of 35 and 55 and represent the financial benefits paid by parents for their children living in a common household. Fathers pay a larger share of the contributions because of their higher income. According to the NTA method, the total private financial support within households are estimated at about 34 billion euros. Of this amount, about 21 billion euros is financial support to persons under 25. By comparison, government expenditure on pensions amounts to 48 billion euros. However, the private intra-family financial support is financed by the relatively small group of parents with dependent children.

Figure 1: Age-specific financial support within families, Austria 2015 (transfers of money and purchased goods/services)

Intergenerational Transfers through Unpaid Services

A large part of intergenerational support in families consists of services provided in the household for personal consumption. These include household work for other generations, as well as childcare and other care services. Estimates of the economic value of these transfers are based on data from the Time Use Survey. Time use surveys record in detail all activities carried out during the course of the day A considerable share of these activities consist of work that is carried out for other household members.

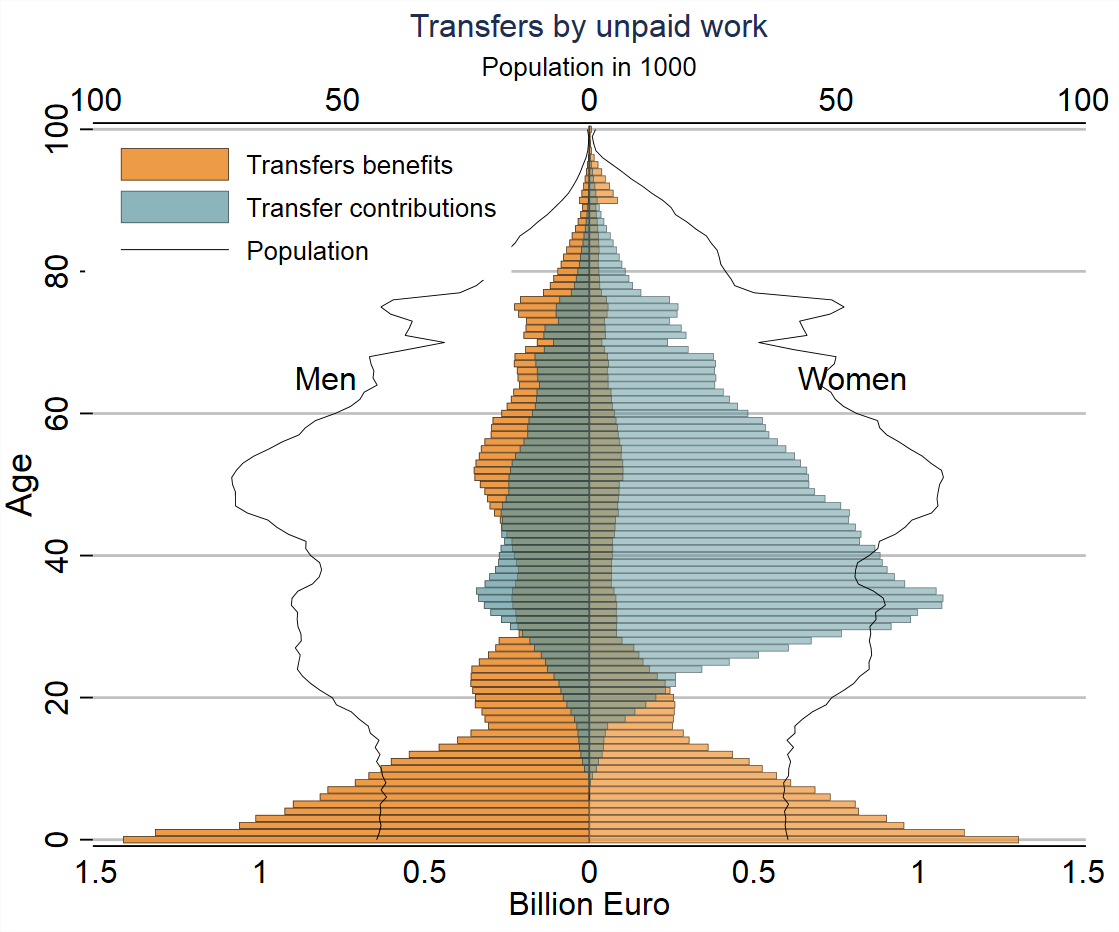

In the first years of life, children require almost seven hours of time from their parents per day. Women aged 30 to 40 years—especially mothers—are the main producers of intergenerational support through unpaid work. On average, women aged 30-40 provide over three hours of work per day for their partners and other household members, in particular the children. For men it is just under one hour at the age of 35. So, while men finance a larger share of the market consumption of a household because of their higher income, women perform a larger share of unpaid work. The monetary value of these benefits can be estimated by valuing the time spent with wages for similar activities. If gross wages for household staff and childcare workers are used, the value of these benefits is 29 billion euros provided to children under 25 (Figure 2). Most of this support is provided by women aged 25-45.

Figure 2: Age-specific transfers within families, Austria 2015 (support of services generated by unpaid work)

Comparing the Family and the State

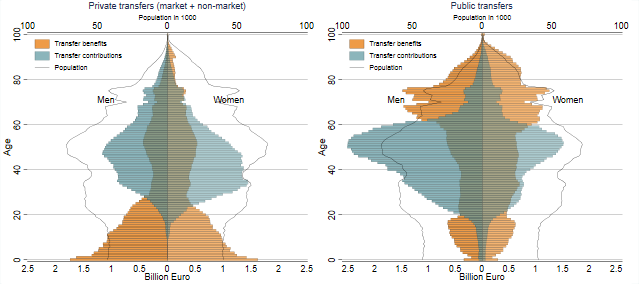

Intergenerational transfers within the family support the younger generation, while state transfers support the older generation. The combination of the two types of intra-family transfers (figures 1+2) allows for a comprehensive presentation of family benefits. Figure 3 shows the private transfers made and received as well as those of the state sector.

Total private transfers amount to 81 billion euros, and public transfers to 123 billion euros. Intra-family transfers are mainly provided by the young working population, public transfers are provided by the older working age population. The public transfers are aimed at the older population, while private transfers aim at the younger generations. The value of total private transfers to the population under 25 is approximately 50 billion euros, while state transfers are worth 25 billion euros. For a comparison, the total state transfers to the population 60+ amount to approximately 58 billion euros, and those of private transfers to 11 billion euros.

Figure 3: Intergenerational transfers by age and gender: comparing the family and the state

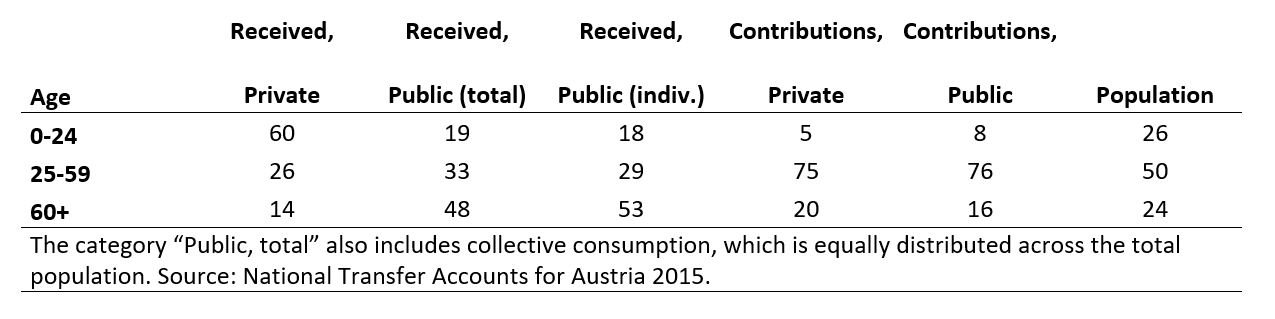

The differences between private and public transfers become clear when the total transfers received are broken down by age group. About 60 percent of total private transfers are paid to the population under 25 years of age, and only 14 percent to the 60+ age group. Conversely, almost half of the state transfer payments are directed to the 60+ age group, and only 19 percent to the population under age 25. The amount of intergenerational redistribution directed to the older population through state transfers becomes even clearer if only individual consumption and social benefits in cash are taken into account and collective state consumption (including administration, security, public order, legislation, infrastructure) is disregarded. The most important components here are pensions (45% of all individual state benefits), health and long-term care services (25%), and education (15%). The under 25 population receives 18% of the state individual benefits, 25- to 59-year-olds approximately 29%, and those over 60 receive 53% of individual benefits. Those under 24-year-olds and those over 60-year-old account for about a quarter of the total population. Table 1 shows the exact distribution by age group of state and private transfers made and received.

Table 1: Distribution of total transfers made and received by age groups. Figures represent a percentage of total benefits.

It should also be noted that private transfers between adults are not independent of transfers to children. Private transfer among adults consist mainly of financial support (transfers) between partners. These intra-family transfers are due to specialization in paid work (mostly fathers) and unpaid work (mostly mothers) due to childcare obligations.

Both state and private intergenerational support services are provided mainly by the population aged 25 to 59. Of particular interest for future development is the contribution of the baby boomer (cohorts born in the 1960s) to total taxes and contributions: Almost 30 percent of all taxes are accounted for by the baby boomers born in the 1960s. The retirement of the baby boomer will therefore pose a major challenge for the Austrian economy and the public transfer system. Between 2025 and 2034, highly populated birth cohorts with about 130,000 people will leave the labor market, while less populated birth cohorts with less than 100,000 people will move up.

Families under Pressure

The economic transfers to children are an essential element of the intergenerational contract. Families take care of the needs of the children and support them up to economic independence and beyond. These services are important investments in the human capital of a society, as children are also future producers and taxpayers. Whether the very generous pension systems can continue to be financed in the future depends to a large extent on the investment of families in children. This relationship is often described as a contract between generations: comprehensive and generous pension provision requires investment in younger generations and future contributors.

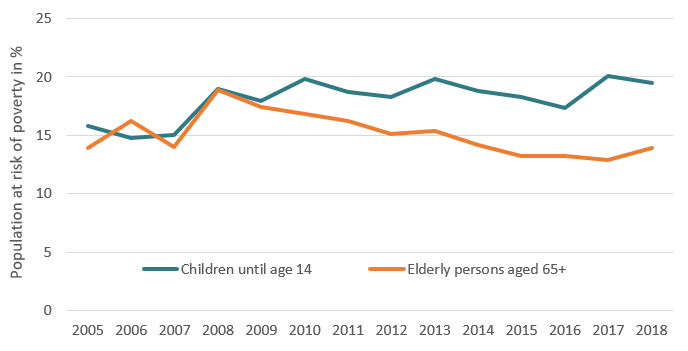

Figure 4: At-risk-of-poverty of children and persons aged 65+ [;] Development over time

The financial viability of the intergenerational transfer system of the private sector is more at risk than that of the state sector. Economic developments over the past decade have led to stagnation or even a decline in the real incomes of younger generations, while pension incomes have risen sharply. Consequently, the at-risk-of-poverty rates for families stagnated at a high level, while the at-risk-of-poverty rate for older persons has fallen sharply (Figure 4). This also means that it is becoming more difficult for young people to follow through with plans to start a family and have children. Estimates of the considerable economic achievements of families make it clear why economic difficulties have an impact on family planning decisions.

A forward-looking structuring of society requires concern and attention to families and the benefits they provide for children, adolescents, and young adults. This also includes offering economic opportunities to young adults. The decision to have a family also depends on the possibilities of combining family and career as well as being able to cope economically with the expense. Reducing bureaucratic obstacles, promoting entrepreneurship, and lowering taxes on wage income are important actions for creating opportunities for young people. Another important point would be to take account of family benefits in pension provision: despite the benefits families provide for future contributors, they are disadvantaged in the pension system. Due to care responsibilities and the resulting low labor force participation, parents have lower pension entitlements than childless couples.

The system of intergenerational transfers requires that a balance be struck between transfers to children and benefits for older generations. Economic crises and an ageing population are increasingly upsetting this balance. The data on financial support within the family should serve to draw attention back to younger generations and the extremely important services that families provide.

Note:

[1] The term transfer refers to a transaction, i.e. a transfer of goods, services, or money without explicit compensation.

More information about National Transfer Accounts (NTAs) and data can be found on the homepage of the NTA project: www.ntaccounts.org. The method and results are also summarized in the book Population Aging and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective (Free download: https://www.idrc.ca/en/book/population-aging-and-generational-economy-global-perspective). European NTA data for 2010 are available at www.wittgensteincentre.org/ntadata. Austrian data for 2015 is still provisional but will also be made publicly available soon.

Translation from German Thomas and Kira Howes